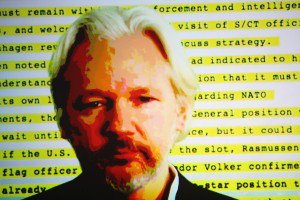

Julian Assange (Photo by Hannah Peters/Getty Images)

Since early May, a terrifying ordeal has been playing out in San Francisco. A journalist, Bryan Carmody, had his home raided by the San Francisco police department after he refused to divulge a confidential source. This was an objectively deplorable raid for a couple of reasons.

First, in the infamous Pentagon Papers case, members of the United States Supreme Court noted that “[b]oth the history and language of the First Amendment” supported the view that the press must “be left free to publish news, whatever the source, without censorship, injunctions, or prior restraints.” In the press world, Bryan Carmody “is what’s known as a stringer,” a person who collects material and provides it to news organizations. In other words, Carmody is not a source; he is, by his very nature, a reporter of information and deserving of First Amendment protection. Secondly, California has a shield law that protects the confidentiality of Carmody’s sources.

Given the First Amendment implications and the state specific protection, the fact that not one but two judges signed-off on the raid of Carmody’s home amounts to nothing less than a judicial disgrace. A disturbing failure by the California magistrates to adequately protect a journalist from unjust detainment and gross abuse of state power. The judicial sign-off to the raid is also the product of a grossly abused Fourth Amendment standard that lacks meaningful judicial oversight and is regularly satisfied by incredibly flawed evidence with absurdly high error rates.

The only encouraging fact about the Carmody story is that in an era where the current president regularly calls the press the enemy of the people, the state’s actions towards Carmody have been almost universally condemned, including by right-wing leading publications. The undeniable result of the widespread condemnation is that Carmody had his documents returned, and the police were forced to concede the raid and the warrants were illegal. In another case involving a publisher of information however, and one that you might have heard of involving Julian Assange, the widespread reaction to the actions of the government could not be any more different.

For those who are unaware, Julian Assange is the head of Wikileaks, an organization that regularly publishes dangerous and damning material, and that the CIA describes as a “non-state hostile intelligence service.” Just recently, Assange was charged by the United States for multiple felonies and again, unlike the Carmody story, many instead view the government’s actions as justified. For example, to David French at the National Review, Assange should not even be considered a member of the press. This is because, as French argues, Assange isn’t doing “what the ‘media’ should do, unless you think the media should publish sailing schedules of troop transports in the face of a submarine threat — or that the media should publish military plans on the eve of an offensive.”

The fundamental problem with French’s view, as pointed out by Jacob Sullum at Reason, is that whether Assange behaves as a member of the traditional media or not is irrelevant. First Amendment protection is thankfully not based on a categorical and vague distinction of “media.” An originalist, historical analysis of how freedom of press was understood at the time of the founding reveals that constitutional protection was intended for all who utilize the written word for mass publication.

Accordingly, to those such as Sullum, the prosecution of Julian Assange represents a troubling assault on the free press, akin to what happened to Carmody, per Sullum:

Counts 9 through 17 involve “disclosure of national defense information,” a felony punishable by up 10 years in prison. That penalty applies to anyone who “willfully communicates, delivers, transmits or causes to be communicated” such information to “any person not entitled to receive it.” This felony is the bread and butter of any journalist who covers national security issues and publishes information that the government would prefer to keep secret.

As First Amendment scholars have noted, that statute squarely applies to indisputably valuable journalism such as publication of the Pentagon Papers.

Although I agree with Sullum that the statute he references is far too broad and unconstitutionally criminalizes a core function of the press, I disagree that Assange cannot be held criminally liable for his actions at Wikileaks.

To be absolutely clear, it is not the act of Assange publishing factual national defense information that I find to be criminal. If that were the case, then every major publication in the country can be classified as a criminal organization and the free press would cease to exist. The criminal act that could be properly attached to Assange, in my opinion, is his alleged “active participation” in the theft of the information published by Wikileaks. As part of its indictment, the Department of Justice is alleging that Assange tried to help Chelsea Manning hack into classified systems. If true, this sort of active participation goes beyond simply publishing information and thus, beyond the scope of protection afforded to the press by the constitution.

Unfortunately, it appears that the prosecution of Assange goes further than his alleged assistance in the theft of the information and seeks to criminalize the publication of information. Therefore, even if an important distinction between the actions of Carmody and Assange can be made, the prosecution of Assange remains every bit as troubling and dangerous to freedom of the press as Sullum claims.

Tyler Broker’s work has been published in the Gonzaga Law Review, the Albany Law Review, and is forthcoming in the University of Memphis Law Review. Feel free to email him or follow him on Twitter to discuss his column.

Tyler Broker’s work has been published in the Gonzaga Law Review, the Albany Law Review, and is forthcoming in the University of Memphis Law Review. Feel free to email him or follow him on Twitter to discuss his column.