Yes, we did love Robert Mugabe once – I perhaps more than others. We met in 1974 – I was 27, an idealistic young journalist, he, nearing 50, the iconic nationalist leader, embodiment of black hopes for justice and equality, just out of prison after 11 years’ incarceration without trial by Ian Smith‘s racial supremacists. He became my friend. I wrote his first biography – introducing him to the world through the syndication of the Argus Group.

But I find it hard to mourn him today. No tears have come. But I’m not celebrating either. My overall emotion is deep sadness – at what might have been, what should have been. Deep sorrow at the loss of it all, the waste of it all.

The horrors of Mugabe’s almost 40-year rule are well documented: bloodshed, injustice, the Gukurahundi massacres in Matabeleland, the brutal Murambatsvina bulldozing of the homes of the poor, stolen elections and ghastly election violence, violent land invasions and the destruction of a vibrant agricultural industry, the world’s highest inflation, 90% unemployment – to mention but a few. While all these were done on his watch, there is heated debate about the extent of his culpability – and consequently the nature of his legacy. Shakespeare’s Mark Antony said, ‘The evil that men do lives after them; The good is oft interred with their bones.’ Will Mugabe be reviled or revered by future generations?

On many occasions he was enthusiastically applauded by African audiences at international fora as an African hero, railing at the West, withdrawing Zimbabwe from the Commonwealth, insulting world leaders and daring to take the white man down a peg or two – even as Zimbabweans were suffering appalling human rights abuses and deprivation at home.

Even in death, he is still a divisive force. Social media today is awash with contradictory narratives and bitter disputes. One group maintains Mugabe ruined the beautiful and well-endowed country he liberated from colonial rule in 1980, reducing it to a begging bowl – with more than a quarter of the population in exile and where the world’s highest inflation and lowest life expectancy have reduced the noble ambitions of majority rule to blood-stained tatters.

Another hails his achievements, notably the liberation of the country from colonial rule, and progress in education and health for all in the early years. Even land reform, although bloody, chaotic and corrupt, has its defenders. And to be sure – land is now in the hands of blacks rather than whites, and the economy is largely under black control.

When and how did it all go so wrong? Other than absolute power corrupting absolutely, there are a few key turning points: the death of his Ghanaian-born wife Sally in 1992 was one. In 1996 he married his secretary Grace, with whom he already had two children. Forty years his junior, Grace was avaricious and ambitious, and her influence over the ageing, ailing Mugabe grew alarmingly to the point where she almost became Vice-President a few years ago.

The formation of the opposition Movement for Democratic Change in 1999 put paid to his ambitions for a one-party state, and he regarded this as a major, personal insult. This was followed in 2000 by his loss of the constitutional referendum by which he sought to increase his presidential powers. His increasingly repressive regime met this setback with a ferocious reign of terror. Human rights were trampled on, the judiciary was emasculated, the independent media was gagged and the country turned into a virtual police state. Hordes of marauding youths recruited into state-funded militias, were unleashed to pillage, rape, beat and otherwise harass the defenceless, largely rural, population into submission to the ruling Zimbabwe African National Union-Patriotic Front.

Mugabe himself became increasingly intolerant of any form of criticism. I last saw him when I sat in the front row of a press conference in 2000 to launch his election campaign. By then, he had come to regard me as his enemy, because of my role in launching the independent Daily News, which was critical of his administration. He would not look at me. I remember the feelings of betrayal, disappointment and sadness that almost choked me. That was the day I mourned the death of my Robert Mugabe.

Shortly thereafter he played his ‘land reform’ card. Together with a rabble of so-called war veterans, the militias were used to invade more than 80% of commercial farming property in the name of returning land ‘stolen by white settlers to the people (black)’. What was seldom noted during the international media outcry at the time, was that more than 200 black farm workers were killed during the invasions in addition to the eight white farmers who made the headlines. Thousands more were beaten, tortured, raped and made homeless.

Beneath the racial/anti-colonial rhetoric lay a far more sinister truth. All those killed, black and white, had one thing in common – they were supporters of the MDC.

Mugabe increasingly disrespected the rule of law – threatening judges, refusing to obey court orders, and filling the bench with his sympathisers, who were given plasma television sets, farms, luxury vehicles and other perks.

Within a few years, Zimbabwe fell from its position as one of the most prosperous and hopeful of African nations to that of a basket case. The health and education systems, together with the sophisticated and diversified agricultural industry – once the pride of the region – collapsed. Some 25% of the population of 12 million – the intellectual and professional cream – left the country.

Following the coup that deposed Mugabe in late 2017, a new word was coined in Zimbabwe – ‘Mugabeism’. It stood for all that destroyed the ‘jewel of Africa’: systemic corruption, vote-rigging, human rights abuses, rampant nepotism and looting of state resources by those in power.

The key task facing Mugabe’s successor, Emmerson Mnangagwa, was to dismantle the entire patronage system, a complex web of intrigue, deceit, corruption and cruelty, with tentacles reaching through every echelon of society and every department of government. He has failed dismally to make inroads into any aspect of Mugabeism. The sad fact is that little has changed since the Mugabe era.

Holding free and fair elections is still pretty much impossible, given the wholesale Mugabeism that permeates the electoral process – from jerrymandering constituency boundaries to the wholesale falsification of the voters’ roll (which includes thousands of duplicates, thousands of dead people and thousands of people over 100 years of age), and the militarisation of the secretariat of the Zimbabwe Electoral Commission. All this has seen our elections rigged, stolen and characterised by mass intimidation and violence for almost four decades – and nothing has changed.

As for the Gukurahundi massacres, Mnangagwa has made some superficial gestures such as allowing people to set up discussion groups (which was taboo under Mugabe). But the chances of a true and rightful reckoning – even with Mugabe dead and buried – are slim. The thing is, it was the Mugabe regime that perpetrated all these horrors. And the machinery of the Mugabe regime – the greedy old men addicted to power, the military, the militias, the youths, and the gravy train riders – is all still intact.

However, the head is now dead. Mugabe’s very existence – even as a decrepit old man in a hospital bed thousands of miles away from home – was a significant reality in the Zimbabwean psyche. Now that we are finally free of that oppressive presence, will we walk out into the sunshine or will we stay behind the bars?

Wilf Mbanga, 6 September, 2019

|

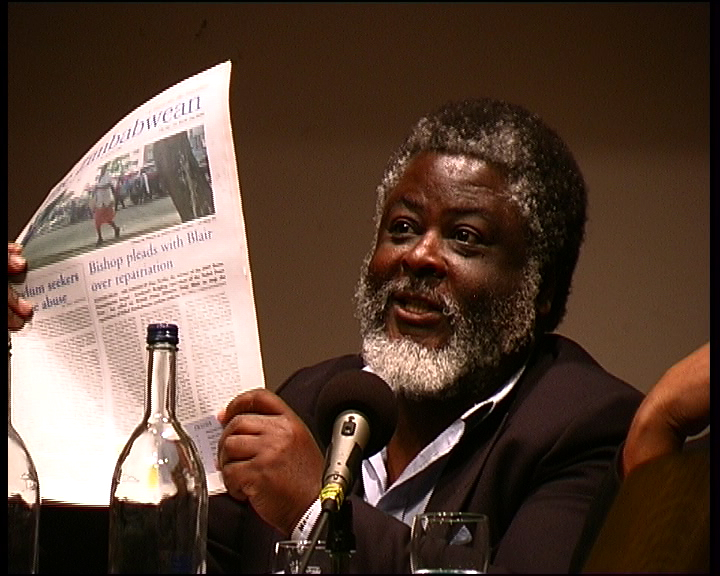

Mbanga in exile 20 years later, after he had fallen out with the Zimbabwean President |

WILF MBANGA WAS THE FOUNDER OF ZIMBABWE’S THE DAILY NEWS, FOUNDER AND EDITOR OF THE ZIMBABWEAN AND THE ZIMBABWEAN ON SUNDAY, ZIMBABWE’S LARGEST CIRCULATION INDEPENDENT NEWSPAPERS BETWEEN 2006 AND 2012. HE LIVED IN EXILE FROM 2005 TO 2018 AFTER BEING DECLARED AN ‘ENEMY OF THE PEOPLE’ BY THE MUGABE REGIME IN 2004 FOR DENOUNCING ITS INCREASINGLY REPRESSIVE TENDENCIES.

Post published in: Featured