BBC Future has brought you in-depth and rigorous stories to help you navigate the current pandemic, but we know that’s not all you want to read. So now we’re dedicating a series to help you escape. We’ll be revisiting our most popular features from the last three years in our Lockdown Longreads.

You’ll find everything from the story about the world’s greatest space mission to the truth about whether our cats really love us, the epic hunt to bring illegal fishermen to justice and the small team which brings long-buried World War Two tanks back to life. What you won’t find is any reference to, well, you-know-what. Enjoy.

Late one evening, Dixon Chibanda, a psychiatrist in Harare, Zimbabwe, received a call from a doctor in an emergency room. A 26-year-old woman named Erica who Chibanda had treated months before had attempted suicide. The doctor said he needed Chibanda’s help to make sure Erica didn’t try it again.

Erica was at a hospital more than 100 miles (160km) away, however, so Chibanda and her mother came up with a plan by phone. As soon as Erica was released from the hospital she and her mother would come see Chibanda to reevaluate her treatment plan.

A week passed, and then two more, with no word from Erica. Finally, Chibanda received a call from her mother. Erica, she told him, had killed herself three days before.

“Why didn’t you come to Harare?” Chibanda asked. “We had agreed that as soon as she’s released, you will come to me!”

“We didn’t have the $15 bus fare to come to Harare,” her mother replied.

The response left him speechless. In the months that followed, Chibanda found himself haunted by the case. He also knew that Erica’s inability to access care due to distance and cost was not exceptional but, in many countries, in fact was the norm.

The grandmother volunteers come to the project with no medical training, but they get results (Credit: Cynthia R Matonhodze)

Globally, more than 300 million people suffer from depression, according to the World Health Organization. Depression is the world’s leading cause of disability and it contributes to 800,000 suicides per year, the majority of which occur in developing countries.

No one knows how many Zimbabweans suffer from kufungisisa, the local word for depression (literally, “thinking too much” in Shona). But Chibanda is certain the number is high. “In Zimbabwe, we like to say that we have four generations of psychological trauma,” he says, citing the Rhodesian Bush War, the Matabeleland massacre and other atrocities.

Yet those suffering from depression have few options due to a dearth of mental health professionals. Chibanda, who is director of the African Mental Health Research Initiative and an associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Zimbabwe and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, is one of just 12 psychiatrists practising in Zimbabwe – a country of over 16 million. Such grim statistics are typical in Sub-Saharan Africa, where the ratio of psychiatrists and psychologists to citizens is one for every 1.5 million. “Some countries don’t even have a single psychiatrist,” Chibanda says.

Since 2006, Chibanda and his team have trained over 400 grandmothers in evidence-based talk therapy (Credit: Cynthia R Matonhodze)

In brainstorming how to tackle this problem, he arrived at an unlikely solution: grandmothers. Since 2006, Chibanda and his team have trained over 400 of the grandmothers in evidence-based talk therapy, which they deliver for free in more than 70 communities in Zimbabwe. In 2017 alone, the Friendship Bench, as the programme is called, helped over 30,000 people there. The method has been empirically vetted and have been expanded to countries beyond, including the US.

The programme, Chibanda believes, can serve as a blueprint for any community, city or country interested in bringing affordable, accessible and highly effective mental health services to its residents. As Chibanda puts it: “Imagine if we could create a global network of grandmothers in every major city in the world.”

Chibanda always knew he wanted to become a doctor, but dermatology and pediatrics were his original interests. Tragedy awakened him to his calling as a psychiatrist. While in medical school in the Czech Republic, a classmate killed himself. “He was a very cheerful chap – no one expected this guy to harm himself and end his life,” he says. “But apparently he was depressed, and none of us picked up on it.”

Chibanda became a psychiatrist. But it wasn’t until Operation Murambatsvina (“remove the filth”), a 2005 government campaign to forcibly clear slums, which left 700,000 people homeless, that he realised the scale of the problem in Zimbabwe. When he ventured into communities after the campaign, he discovered “extremely high” rates of post-traumatic stress disorder and other mental health issues.

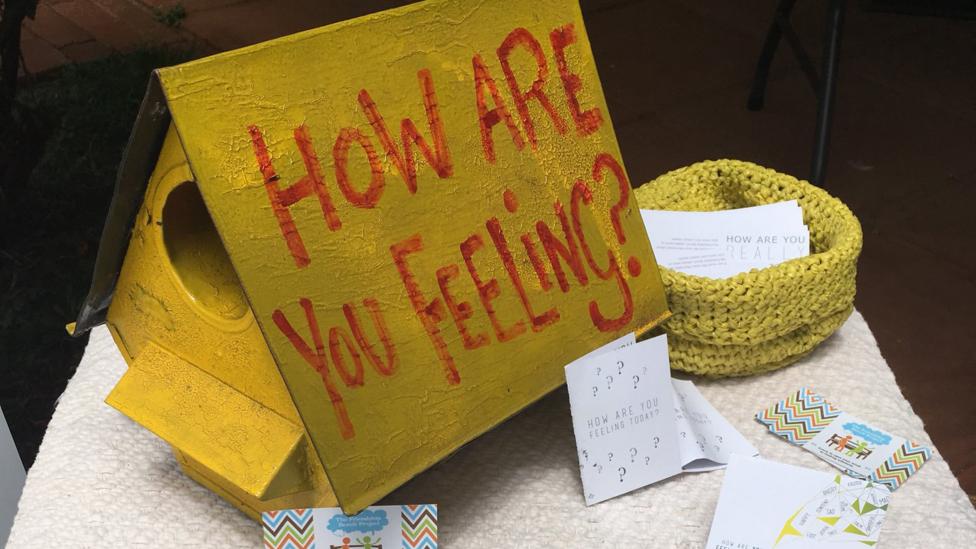

Opening up mental health conversations in Zimbabwe (Credit: The Friendship Bench Zimbabwe)

In the midst of this work, Erica killed herself, bringing extra urgency to Chibanda’s quest to find a solution for ordinary Zimbabweans.

Chibanda was the only psychiatrist in the country working in the public health space, but his supervisors told him that there were no resources they could give him. All of the nurses were too busy with HIV-related issues and maternal and child health care, and all the rooms at the local clinic were full. They could, however, give him 14 grandmothers and provide access to the space outside.

Rather than throw up his hands, though, Chibanda came up with the idea for the friendship bench. “A lot of people think I’m a genius for thinking of this, but it’s not true,” he says. “I just had to work with what was there.”

That’s not to say that Chibanda initially believed it would work, though. The grandmothers, who were community volunteers, had no experience in mental health counselling and most had minimal education. “I was sceptical about using old women,” he admits. Nor was he the only one with misgivings. “A lot of people thought it was a ridiculous idea,” he says. “My colleagues told me, ‘This is nonsense.’”

Lacking any other option, though, Chibanda began training the grandmothers as best he could. At first, he tried to adhere to the medical terminology developed in the West, using words like “depression” and “suicidal ideation”. But the grandmothers told him this wouldn’t work. In order to reach people, they insisted, they needed to communicate through culturally rooted concepts that people can identify with. They needed, in other words, to speak the language of their patients. So in addition to the formal training the received, they worked together to incorporate Shona concepts of opening up the mind, and uplifting and strengthening the spirit.

“The training package itself is rooted in evidence-based therapy, but it’s also equally rooted in indigenous concepts,” Chibanda says. “I think that’s largely one of the reasons it’s been successful, because it’s really managed to bring together these different pieces using local knowledge and wisdom.”

Efficacious and replicable

As I stepped out of the car, Rudo Chinhoyi, a tiny woman with an easy smile and dusting of white hair, rushed out of her cinderblock house to meet me. “Hello!” she beamed, throwing her arms around me. “How are you doing? Welcome!”

Grandmother Chinhoyi, as she is known around here, has been with the Friendship Bench programme from the start. “I joined this programme because I wanted to help people in the community,” she says. “It was too much – the depressed people. There were so many of them and I wanted to reduce the numbers.”

“I’ve always been like that, wanting to help others,” she adds with a smile and a shrug. “I value human beings so much.”

Grandmother Rudo Chinhoyi, in the blue t-shirt, surrounded by a few of her three children, nine grandchildren and eight great-grandchildren (Credit: Rachel Nuwer)

Chinhoyi, who is 72, has lost count of the number of people she has treated on an almost daily basis over the past 10-plus years. She regularly meets with HIV-positive individuals, drug addicts, people suffering from poverty and hunger, unhappy married couples, lonely older people and pregnant, unmarried young women. Regardless of their background or circumstances, she begins her sessions the same way: “I introduce myself and I say, ‘What is your problem? Tell me everything, and let me help you with my words.’”

After hearing the individual’s story, Chinhoyi guides her patient until he or she arrives at a solution on their own. Then, until their issue is completely resolved, she follows up with the person every few days to make sure they are sticking to the plan.

Once, for example, Chinhoyi met with a man whose wife had just run off with the landlord of their rental home. “The husband wanted to take an axe to attack the couple, but I convinced him not to,” Chinhoyi says. “I told the guy, ‘If you go to prison, your kids will be left alone, it’s not worth it.’” Rather than resort to violence, the man divorced his wife, she says, and is now happily remarried.

Having come from the same communities as their patients, Chinhoyi and the other grandmothers have often lived through the same social traumas. Yet Chibanda and his colleagues have been shocked to find that the grandmothers themselves present surprisingly low rates of post-traumatic stress disorder and other common mental health ailments. “What we see in them is this amazing resilience in the face of adversity,” he says.

A friendship bench in Malawi (Credit: The Friendship Bench Zimbabwe)

Nor do the grandmothers seem to get burnt out despite counselling people on the brink of crisis day after day. “We’re exploring why this is, but what seems to be emerging is this concept of altruism, in which the grandmothers really feel that they get something out of actually making a difference in the lives of others,” Chibanda says. “It gives them a lot of great benefits, too.”

By 2009, Chibanda was already sure the programme was working, both in terms or improving quality of life for participants and reducing suicide. Harare’s city health department, which pays for the programme, was fully on board, and patients were being regularly referred from clinics, schools, the police and more. But if the Friendship Bench was going to be recognised and replicated around the world, Chibanda would first need to prove scientifically that it works.

In 2016, Chibanda – collaborating with colleagues from Zimbabwe and the UK – published the results of a randomised control trial of the programme’s efficacy in the Journal of the American Medical Association. The researchers split 600 people with symptoms of depression into two groups. They found that after six months, the group that had seen the grandmothers had significantly lower symptoms of depression compared to the group that underwent conventional treatment.

“We were thrilled to bits with the results, which showed the intervention is having a big effect on people’s daily lives and ability to function,” says Victoria Simms, an epidemiologist at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and co-author of the study. “It’s about giving people the tools they need to solve their own problems.”

Two more scientific trials are now underway, she adds, including one examining a new Youth Friendship Bench programme in Harare and another set up specifically for young people who are HIV-positive.

The programme has also expanded to several countries, and in doing so, Chibanda and his colleagues have found not only that it translates well across cultures but also that grandmothers aren’t the only ones capable of giving effective counseling. In Malawi, the Friendship Bench uses elderly counsellors of both genders, while Zanzibar uses younger men and women. New York City’s counsellors are the most diverse, including individuals of all ages and races, some of whom come from the LGBTQ community. “We cover all the bases,” says Takeesha White, executive director of the Office of Strategic Planning and Communications at the NYC Department of Health’s Center for Health Equity. “New York City’s population is very broad.”

The programme, Chibanda believes, can serve as a blueprint for any community (Credit: The Friendship Bench Zimbabwe)

Many of the New York counsellors have successfully overcome addictions and other life challenges themselves. “We’re committed to having folks with lived experiences, who can speak the language of recovery and of dealing with addiction,” White says. “Before you know it, you’re not on a bench, you’re just inside of a warm conversation with someone who cares and understands.”

The New York City benches – which are bright orange – were piloted in 2016 and launched in mid-2017, attracting some 30,000 visitors during their first year. The city so far has three permanent benches in the Bronx, Brooklyn and Harlem, and the programme hosts pop-ups at festivals, churches, food pantries, parks and more. Friendship Bench counsellors also make themselves available immediately following community tragedies, including a recent suicide completed in public in East Harlem.

“When I visited New York, I was pleasantly surprised to find that the issues New Yorkers deal with are very similar to the issues here in Zimbabwe,” Chibanda says. “It’s issues related to loneliness, to access to care, and to just being able to know that what you’re experiencing is treatable.”

While many more psychiatrists work in New York City than in Zimbabwe, the ratio of doctors to residents – about one for every 6,000 people in New York – is still problematic for providing access to care, especially for the underprivileged. The same holds true in many other places around the world, including the UK, which is now considering rolling out a Friendship Bench programme in London.

“This isn’t just a solution for low-income countries,” Simms says. “This may well be a solution that every country in the world could benefit from.”