Two years ago, a working group at Airbus called ContractInnovators began investigating how they could design better contracts. As a use case, they set about redesigning a Non-Disclosure Agreement (NDA).

The goal of the group was not to create a legal document that could extract more concessions from business partners or better protect Airbus in case of litigation.

Rather, the goal was to create a contract people could understand, enabling faster onboarding for vendors.

It’s often taken for granted that contracts are impossible for a layperson to decipher. Research from the International Association for Contract & Commercial Management (IACCM) shows that 88 percent of contract users find contracts “difficult or impossible to understand.” That’s what lawyers are for, right?

The Airbus group, led by Ines Curtius, Head of Contract Governance, Space Systems, refused to accept this status quo. With the world of business digitizing and accelerating, Curtius and her cohort recognized that contracting had to keep up.

“We needed to be faster and more agile,” Ines said during a recent webinar, hosted by IACCM and Icertis.

Ines’s team started from the ground up on what a contract could look like.

What they came up with was an NDA that used far fewer words and employed visual representations to convey the meaning of the document. The information on the business process was captured in a single page, and its “readability,” as measured by the Flesch Readability Score, rose from 22 to 51.

Ines still recalls the reaction she got when she first showed the new NDA to an Airbus supplier: a smile.

“Have you ever encountered your contractual partner smiling going through your contractual draft?” Ines asks. “This is showing that they trust you. It is a trust-based business you are building up.”

Visual Contracting: Changing Perspectives on Contracts

In using visual representations within a legal document, Airbus is an early adopter of what will be a growing trend in the years to come: visual contracting.

Broadly speaking, visual contracting is the use of design thinking and technology in combination with diagrams, illustrations, flow charts, hierarchies and other data-visualization tools to express contractual terms, relationships and concepts.

In one of the best-known examples of visual contracting, Royal Dutch Shell included illustrations in a standard contract to express when risk and title of oil are transferred during a delivery. Rather than a sea of dense legalese describing the point of transfer, four simple illustrations explain it.

Who needs a lawyer for that?

Visual Contracting Is More Than Just Cool Pictures

The innovation and artistry around visual contracting are fascinating. But what’s really exciting about the movement is the philosophical shift that it represents.

When a company invests in visual contracting, it’s because they want their contracts to be more than just enforcement tools that are defensible in a court of law. Instead, they want their contracts to convey value between parties. It adds expression and communication to the contracting process.

Visual contracting isn’t just confined to illustration. Visual contracting can be scaled across an entire body of contracts to understand contractual terms and relationships, better leveraging design thinking and technology under the digital transformation program of organizations.

For example, a company can use flow charts to understand how a supplier relationship impacts their ability to deliver a project to a customer. Or perhaps populate a map of where business is being done based on contract metadata. There are future applications of deep learning technology like artificial intelligence as well, to extract contract information with respect to metadata and text out of such graphical illustrated visual contracts.

This is a mindset shift whose time has come. Contracts contain a vast wealth of data about a company’s risks and opportunities. Visual contracting allows these risks and opportunities to be understood intuitively by business users. Doing so unlocks incredible value from what had long been a store of hardly decipherable legal text.

The Nuts and Bolts of Visual Contracting

So how does a company go about implementing visual contracting?

Some tools can help you get started. IACCM has created a wonderful library of contract designs that can inspire teams to think about how they can visually represent their contracts. For example, check out their “Swim Lanes” design.

Creating these contracts may also require the help of a designer to bring visual concepts to life.

If your company is interested in scaling visual contracting across a body of contracts, you will need the help of technology.

Enterprise contract management software pools a company’s contracts and contract data into a single repository, where they can be managed and analyzed holistically. From here, visual representations of contract relationships and processes can be built.

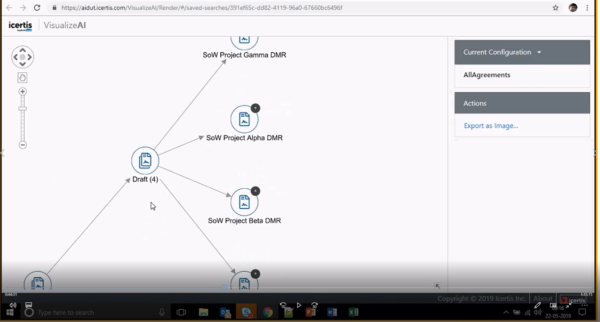

Icertis’s VisualizeAI application, built on top of the Icertis Contract Management (ICM) platform, enables users to quickly find and load a large volume of contract data, navigate relationships and easily discover patterns.

For example, let’s say a supply chain manager wanted to see all the contracts associated with a certain supplier. With VisualizeAI, she can spin up a flow chart that shows all of the company’s contractual relationships with the supplier for intuitive insights into that piece of the supply chain.

She can then take it a step further and display contracts that are dependent on that supplier delivering the goods. Suddenly the contracts are becoming a looking glass into the company’s entire value chain!

Just as with Airbus’s illustrated NDA, VizualizeAI allows companies to transform their contracts into stores of data that convey data.

When contracts and contract information are easy to understand, commerce accelerates, risk is reduced and commercial relationships become more valuable.

This is the power of visualization.

To learn more, view this on-demand webinar: Cut Through the Noise With Visual Contracting.

Tyler Broker’s work has been published in the Gonzaga Law Review, the Albany Law Review, and is forthcoming in the University of Memphis Law Review. Feel free to

Tyler Broker’s work has been published in the Gonzaga Law Review, the Albany Law Review, and is forthcoming in the University of Memphis Law Review. Feel free to

Kathryn Rubino is a Senior Editor at Above the Law, and host of

Kathryn Rubino is a Senior Editor at Above the Law, and host of