The IMF’s recent report makes grim reading, with negative growth recorded for last year, and an expectation of effectively no growth, growing inflation and a devaluing currency into 2020. The underlying macro-economic instability has been made worse by major climate impacts during 2019 – both the drought and cyclone Idai. The situation is bad, and getting worse.

With the failure of government to address the required reforms, the prospects of renewed external support with the necessary debt write-offs look minimal. The stand-off with the international community continues, with international sanctions and a lack of investment continuing. With external public debt rising to over 50% of GDP, much of it in arrears, there is little chance of the Zimbabwean state repaying. Bail-outs at some point will be required, and the scale of investment needed for basic infrastructure and services is estimated at US$16 billion. But instead of Zimbabwe, Somalia seems to be the focus of favourable terms, with Zimbabwe being left to decline further.

The embedded corruption at the heart of state failure becomes intensified as the economic chaos deepens. Those able to profit from parallel currency deals and leverage resource from state-led programmes are the elite few, connected to the political-military elite. And who suffers? Ordinary people, and especially the poor. The consequences of economic collapse are most felt in the urban areas, where safety nets are non-existent. While those in the rural areas have their own production to fall back on; even though this year the effects of drought have hit rural livelihoods hard too.

As the state tries to ameliorate the situation, things only get worse. For example, the Finance Minister announced the creation of ‘garrison shops’ so a restive army could buy goods on favourable terms. It was supposed to be financed by a levy on civil servants. But another parallel economy only creates opportunities for hoarding and profit, and punitive taxation on already struggling people causes resentment. Policy is being made on the hoof. Almost as soon as it was announced, it seems the tax was rescinded, or deemed voluntary, and so a big unbudgeted expenditure was added to the inflation pressures.

The uncovering of the massive rent-seeking in the milling industry, directly fuelled by state-sponsored grain buying for food relief, has exposed the problems. An apparently well-meaning policy is naively implemented, and those in the system exploit its benefits ruthlessly. In this case, with many alleged connections right to the top. The sense that those in charge are wholly out their depth or exploiting the system for their own benefit (or possibly both) is palpable. The IMF review team, in appropriately guarded language, clearly felt this.

Mentioned only obliquely was the cause celebre of this chaos – command agriculture. The corruption at the heart of this programme has been widely exposed, not least by the Public Accounts committee, chaired by opposition MP, Tendai Biti. Around US$3 billion is alleged to have been misused, through a complex web of government funding, private companies and military involvement. A recent ZDI report has highlighted the nexus of corruption at the heart of the party-state and military.

Under normal circumstances a public-private partnership for contract financing of commercial agriculture would have some credibility – just as would subsidised produce for the armed forces or state purchasing of grain through milling companies. But circumstances aren’t normal in Zimbabwe. Despite attempts at restructuring, the grip of corruption is so intense, and often led by networks close to those in power and running these initiatives, that these apparently sensible schemes become the basis for significant extraction, no matter what their worth.

No-one has quite got to the bottom of the command agriculture story as yet. The political economy is clear, but there have certainly been benefits. In our study areas for example, command agriculture resources have unquestionably resulted in boosts in production, especially on A2 farms. Repayments have been inconsistent, but many have been pursued rigorously. Not everyone can get away with just exploiting the system. But this is the point – it is just a few that continue to profit, getting massively rich while the rest suffer.

Is there a way out of this downward spiral? Attempts by the technocrats in the state to do what is required are foiled with each move it seems. Policies seem to be concocted at random, desperately responding to situation that is out of hand. One day it was illegal to sell fuel in US dollars to protect the local currency, the next day it is permitted across the country. Secret printing of money to offset US dollar losses in the mining industry solve one problem, but create many others.

The loss of trust in the government by key players – the IMF, western donor governments, even the Chinese – is clear. Sanctions (or other ‘restrictive measures’) are still in place, with influential players within and outside Zimbabwe arguing that they should remain until the regime changes. Investors are shying away, despite the occasional positive effort to rebuild key parts of the economy. Moves to create political coalitions across the divides are viewed with great scepticism given the experience of the Government of National Unity from 2009-13. It’s stale-mate. Some are holding out for an ‘uprising’ (usually those sitting in comfort firing off tweets), while others think it will have to get much worse before there is a change.

It is not a happy story, and given the dire food security situation this year, the consequences for livelihoods are severe. In agriculture, the glimmers of progress seen up to 2016 on the back of greater economy stability are fast being stamped out. Things are currently very fragile, and most farmers are holding back on investing further.

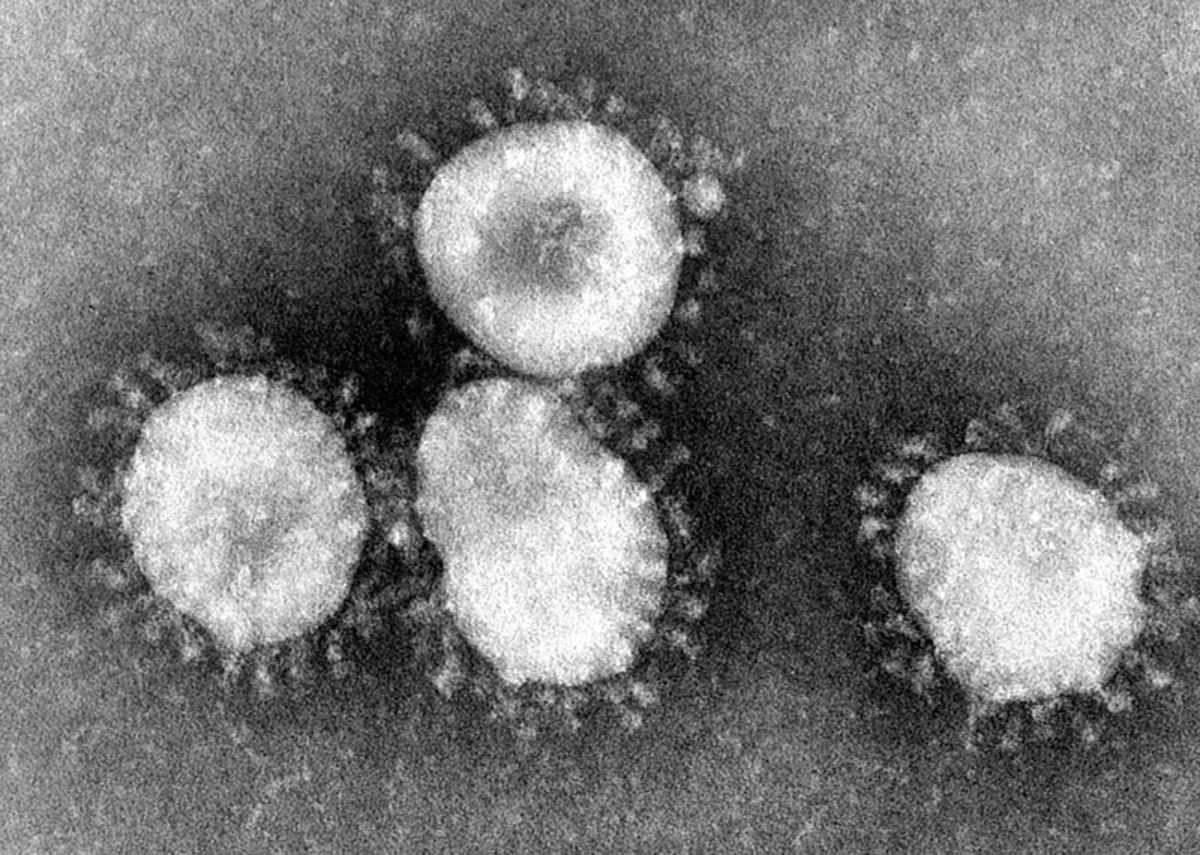

Today, like Somalia, Zimbabwe has a collapsed economy with vanishingly little state capacity, but, unlike Somalia, seems to be unable to convince the IMF, AfDB or other donors and investors to provide support. Another shock – whether further drought, the spread of coronavirus or something else – may create cascading, disastrous effects, with the elite being able to escape, while the poor (and this now includes a large portion of the population) will have to bear the brunt.

This post was written by Ian Scoones and first appeared on Zimbabweland

Post published in: Business

Jordan Rothman is a partner of

Jordan Rothman is a partner of

Kathryn Rubino is a Senior Editor at Above the Law, and host of

Kathryn Rubino is a Senior Editor at Above the Law, and host of