Sorry, folks, but I’m afraid it’s here: the recession. We’ve had a good run, some 128 months of economic expansion — more than a decade, the longest expansion on record. But all good things must come to an end.

Dating economic cycles is by its nature retrospective, so we won’t know that we’re officially in a recession until the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) says so. But if I had to bet, I would wager that we are currently in, or about to enter, an economic downturn.

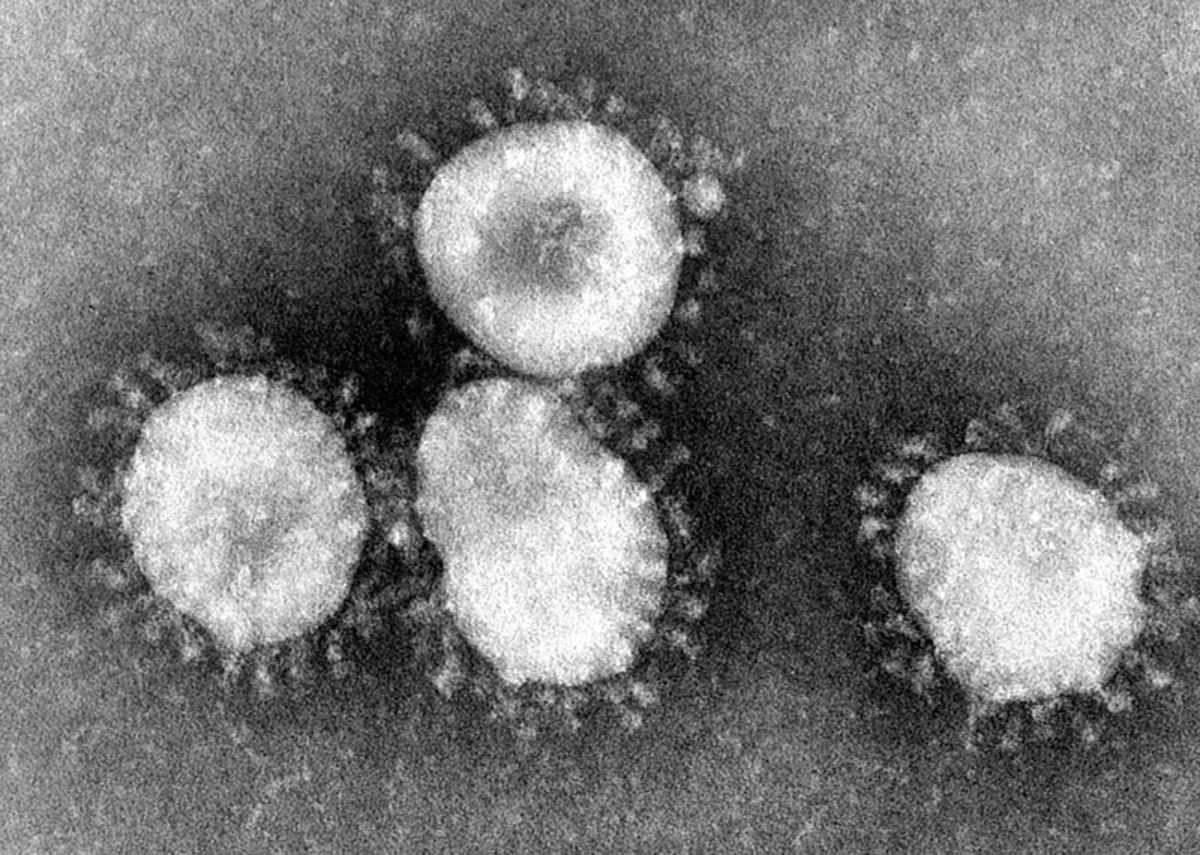

When we look back, this recession will probably be regarded as the “Coronavirus Recession” (or, if you want to be more technical about it, the “Covid-19 Recession”). The worldwide outbreak of coronavirus and the steps taken to combat it are having a serious effect on the global economy, as reflected in the plummeting equity markets (yesterday’s nice little rally notwithstanding).

And as Neil Irwin and others have pointed out, this recession will be especially difficult to address because it involves a “supply shock,” i.e., “a reduction in the economy’s capacity to make things,” as opposed to a “demand shock,” a dip in demand that can be addressed through the conventional tools of monetary and fiscal policy. These tools are already more limited in their power than usual, in light of how low interest rates already are — in the wake of this morning’s emergency rate cut, the target range for the federal funds rate is just 1 percent to 1.25 percent — and how large the federal budget deficit already is.

Without further ado, here are my predictions about what the recession will mean for Biglaw. Take these predictions for whatever they’re worth, since I don’t claim any special power of prognostication. (I certainly didn’t see the last recession coming, and yeah, I thought Hillary was going to win too.)

1. There will be layoffs — but not as many as during the Great Recession.

In the last recession, the so-called “Great Recession,” an estimated 10,000 lawyers in Biglaw, as well as thousands of staff, lost their jobs. The layoffs were, as Kathryn Rubino succinctly described them, “brutal.” On one particularly terrible day that we dubbed “Black Thursday,” almost 1,000 lawyers and staffers lost their jobs.

This recession will also bring layoffs, but I don’t think they’ll be as bad as in the last recession. Why? On the lawyer side, firms haven’t been as profligate with their hiring as they were in the years leading up to the Great Recession (instead preferring to overwork their existing associates before hiring new ones, for better or worse). On the staff side, firms have actually been making cuts over the past few years, using a combination of layoffs and buyouts to trim the ranks.

Conducting layoffs during an economic boom, sending staffers packing as partner profits hit record highs, struck some as harsh and unnecessary. But it will probably mean fewer layoffs during the recession than we would have had otherwise — you can’t cut more once you’ve reached bone.

2. There will be firm collapses — but not as many as during the Great Recession.

A number of Biglaw firms fell apart around the time of the Great Recession or in its wake, as a result of recession-inflicted injuries. Pour some out for Heller, Thelen, Thacher Proffitt & Wood, Howrey, and, of course, dearly departed Dewey.

But many firms have learned lessons from the recession. Since the Great Recession, firms have been seeking greater capital contributions from their partners, reducing their reliance on bank loans and outside credit, cutting back on lavish guarantees to lateral partners, and otherwise shoring up their financials ahead of the coming storm.

Yes, there will be some law firm bankruptcies and dissolutions, but not as many as last time. And some of the firms that will fall would probably have fallen apart anyway, with the recession just acting as an accelerating factor rather than a “but for” cause.

3. Some countercyclical practice areas will pick up — but not as much as one might expect.

The practices that people talk about as somewhat countercyclical, like litigation and bankruptcy, could heat during the recession. But I don’t think they’ll heat up as much as some might think.

Litigation, I fear, is in something of a secular decline. A recession might slow or temporarily reverse this trend, but I don’t know that it will change the overall trajectory.

Litigation is basically eating itself, getting so expensive that it is fueling the rise of alternative forms of dispute resolution and also leading to earlier settlements, instead of the long-running and lucrative courtroom battles that made the practice a moneymaker for so many years. Also, the discovery/e-discovery process that used to be such a cash cow has been disrupted by technology — and made less lucrative, at least for law firms (with legal technology companies and alternative legal service providers capturing some of the lost profits). There’s a reason why I recently wrote, “Mammas, don’t let your babies grow up to be litigators.”

As for bankruptcy, it is also pricing itself out of existence. Obscenely expensive Chapter 11 litigations have led to more (and faster) out-of-court restructurings and prepackaged bankruptcies. Also, remember that interest rates remain quite low — and will go even lower as the Federal Reserve tries to fight the recession. A low-interest rate environment isn’t good for the bankruptcy bar, since it makes it easier for companies to avoid insolvency by finding new sources of credit or by reaching accommodations with their creditors.

So what’s the bottom line? The bad news is that the recession is here or about to arrive; the good news is that it won’t be that bad (at least compared to the Great Recession; there’s a reason we call it “Great”).

This isn’t very exciting, which might be disappointing to some. But after all the excitement of the past few weeks — the twists and turns of the Democratic primary, the worldwide spread of coronavirus, last month’s stock market meltdown — a bit of boredom might be just what the doctor ordered.

Coronavirus, Election Jitters Have Law Firm Leaders Pondering a Downturn [Law.com]

David Lat, the founding editor of Above the Law, is a writer, speaker, and legal recruiter at Lateral Link, where he is a managing director in the New York office. David’s book, Supreme Ambitions: A Novel (2014), was described by the New York Times as “the most buzzed-about novel of the year” among legal elites. David previously worked as a federal prosecutor, a litigation associate at Wachtell Lipton, and a law clerk to Judge Diarmuid F. O’Scannlain of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. You can connect with David on Twitter (@DavidLat), LinkedIn, and Facebook, and you can reach him by email at dlat@laterallink.com.

David Lat, the founding editor of Above the Law, is a writer, speaker, and legal recruiter at Lateral Link, where he is a managing director in the New York office. David’s book, Supreme Ambitions: A Novel (2014), was described by the New York Times as “the most buzzed-about novel of the year” among legal elites. David previously worked as a federal prosecutor, a litigation associate at Wachtell Lipton, and a law clerk to Judge Diarmuid F. O’Scannlain of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. You can connect with David on Twitter (@DavidLat), LinkedIn, and Facebook, and you can reach him by email at dlat@laterallink.com.

Staci Zaretsky is a senior editor at Above the Law, where she’s worked since 2011. She’d love to hear from you, so please feel free to email her with any tips, questions, comments, or critiques. You can follow her on Twitter or connect with her on LinkedIn.

Staci Zaretsky is a senior editor at Above the Law, where she’s worked since 2011. She’d love to hear from you, so please feel free to email her with any tips, questions, comments, or critiques. You can follow her on Twitter or connect with her on LinkedIn.

Lindsay Kennedy recently took a position with Eaker Perez Law, doing exclusively U.S. federal tax law. She is also the Executive Director of

Lindsay Kennedy recently took a position with Eaker Perez Law, doing exclusively U.S. federal tax law. She is also the Executive Director of

Jordan Rothman is a partner of

Jordan Rothman is a partner of