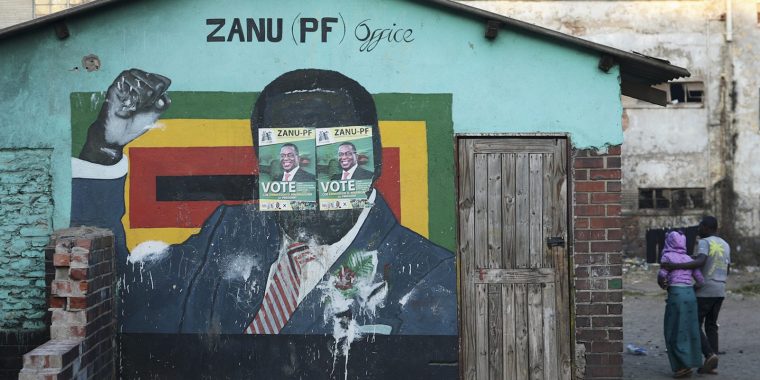

South Africa is a regional force and a close neighbour whose economic, diplomatic and moral influence should be brought to bear on Zimbabwe in order to bring about change. (Photo by Dan Kitwood/Getty Images)

When Robert Mugabe was removed from power in a civilian-assisted Zimbabwean military coup in 2017, it presented a narrow window of opportunity to transform the country into a real democracy. The appointment of Emmerson Mnangagwa, who claimed to be as “soft as wool”, as the new president was a masterstroke move by the army. It confounded critics and earned the coup the support of the African Union (AU) and the Southern African Development Community (SADC).

Critics who pointed out that this was a coup and that a military state was in the making were drowned out by a chorus from a “give-ED-a-chance” brigade, comprised of prominent businesspeople, diplomats, Zanu-PF supporters and some ordinary people. Many mistakenly equated the removal of Mugabe the person with the dismantling of Mugabe the system. The momentum generated by the removal of Mugabe by the army was long enough to give Zanu-PF another controversial electoral victory in the 2018 elections.

The role of Thabo Mbeki in covering up for Zanu-PF

South Africa is a regional force and a close neighbour whose economic, diplomatic and moral influence should be brought to bear on Zimbabwe in order to bring about change — even though it may be controversial change.

But sadly, despite its own human rights-centred Constitution, for the past 20 years South Africa has not used that influence to advance democracy and rights in Zimbabwe. In fact, it has done the opposite.

The lowlight was the role played by former president Thabo Mbeki in negotiating a delicate Government of National Unity between Zanu-PF and opposition parties after Zanu-PF had lost the 2008 elections. A lot of people view the 2008 intervention that helped an election loser, Mugabe, to retain power at the expense of the election winner, Morgan Tsvangirai, as a lost opportunity to strengthen democracy in the region. It was also at odds with what has happened in other regions, such as the Economic Community of West African States (Ecowas), where democratic election outcomes have been enforced by regional bodies, as happened in Gambia.

Part of the reason Zanu-PF has not fully embraced the growth of electoral democracy in Zimbabwe may be knowing that the ANC does not believe that any opposition party must win power in Zimbabwe, but instead makes public its desire to help Zanu-PF retain power.

South Africa’s approach towards violations of human rights by its northern neighbour has always been measured and non-confrontational.

When in the early 2000s Mugabe’s Zanu-PF faced the first real threat of loss of power democratically to Morgan Tsvangirai’s MDC and defaulted to the use of organised violence and torture, concerns about human rights violations and abuses were raised. Despite president Mbeki’s knowledge of widespread and systematic use of organised violence and torture to influence electoral outcomes via many sources — including the Judicial Observer Mission on Zimbabwe elections that he commissioned leading to the production of the Khampepe report — Mbeki dismissed claims of rights violations. He argued that there was no crisis in Zimbabwe but just a “regime change agenda” sponsored by the West and that allegations of human rights violations were being used as a pretext for regime change.

That Mbeki took a position of “quiet diplomacy”, knowing full well that Zimbabwe was abusing rights and frustrating free and fair elections was borne out when the Khampepe report was released, confirming that the elections in 2000 and 2002 had been marred by serious irregularities and that they could be declared neither free nor fair.

According to an article in Daily Maverick, the fundamental precepts of South Africa’s policy towards Zimbabwe were set out during the Mbeki presidency: that is, a policy of “quiet diplomacy” that was designed to encourage the Mugabe regime to bring about democratic change via a reformed Zanu-PF.

Managing Mnangagwa: Quiet diplomacy and its discontents

South Africa’s presidents may have changed, but once again in the current crisis in Zimbabwe, its government seems very reluctant to take any action. In fact, it was only jolted into action after sustained domestic, regional and international pressure.

To that end, on 6 August 2020, President Cyril Ramaphosa announced the appointment of former speaker of Parliament Baleka Mbete and former safety and security minister Sydney Mufamadi as special envoys to Zimbabwe to:

“Engage the government of Zimbabwe and relevant stakeholders to identify possible ways in which South Africa can assist Zimbabwe, following recent reports of difficulties that the Republic of Zimbabwe is experiencing.”

True to form, this toned-down diplomatic language was used to refer to serious levels of state repression, manifesting in the arbitrary arrests of journalists, abductions, disappearances and torture of political activists, government critics and human rights defenders.

The most recent clampdown and state-led violence happened as a response to a scheduled 31 July demonstration that had been planned by activists, led by Jacob Ngarivhume of Transform Zimbabwe. The activists maintain the abortive demonstration was meant to be peaceful mass action aimed at voicing concern over corruption and the unbearable economic and social situation that has worsened owing to the Covid-19 pandemic.

From the beginning, the fact that the South African government again opted for a very mild characterisation of the situation as “difficulties” worried many observers who doubted Ramaphosa would take a decisive stance. They saw this softly-softly approach as a sure sign the intervention was not at the level required.

Among them was the Centre for Human Rights at the University of Pretoria which, though appreciating the deployment of the two envoys, regretted “the characterisation of a situation of serious human rights violations as ‘difficulties’ ”, and urged President Ramaphosa to ensure that South Africa’s approach is not one of “quiet diplomacy” at the expense of addressing the underlying issues of impunity and lack of accountability.

As the current chairperson of the AU, hopes were high Ramaphosa would use this platform to at least send a clear message that the actions of the government of Zimbabwe were at wide variance with the agreed norms of democratic governance.

The initial delegation sent by President Ramaphosa arrived in Harare with the intention of consulting with other stakeholders, including opposition parties and other key role players other than Zanu-PF. However, the Zimbabwean government was not interested in any arrangement that would debunk its well-choreographed baseline argument that there was “no crisis”. As a result, the visiting delegation was forced to return to South Africa without meeting anyone else. No communiqué followed this meeting.

President Ramaphosa then decided to send another delegation, this time under the auspices of South Africa’s governing ANC on 8 September.

Liberation war ‘sister parties’: Time for tough love

The party-party approach was justified by the ANC leadership as the perfect approach in dealing with a “sister” revolutionary party to address fundamental domestic issues whose effects are, however, international, including an influx of economic and political refugees into South Africa. Predictably, it seems to have yielded nothing as the final communiqué again avoided the term ‘crisis’. The Zimbabwe government prefers to fool the world that the country is facing only “challenges”, like many other countries affected by Covid-19.

Questions have emerged on the true intentions, mandate and indeed sincerity of the South African government in this latest round of interventions. MDC Alliance vice-president Tendai Biti has criticised the South African envoys for being a political smokescreen with no genuine mandate to remedy the ongoing crisis.

Another crucial question is just how should South Africa be expected to rein in a sovereign state?

When one considers the strong sentiments issued by some members of the ANC delegation soon after its return to South Africa, it is difficult to reconcile this with the statements made by the Zimbabwe government, as both sides seem to be at odds despite emerging from the same meeting.

For example, the South African delegation announced it had agreed with its Zanu-PF counterparts that the next South African delegation would meet the opposition and civil society groups. But in a highly charged press conference, Zanu-PF declared that the ANC would not be allowed to meet the MDC Alliance. Zanu-PF secretary for external affairs Simbarashe Mumbengegwi declared there “is no crisis in Zimbabwe, therefore, the ANC’s mediation is not needed”.

At the same time, Zanu-PF’s acting spokesperson, Patrick Chinamasa, and the president’s spokesperson (via Twitter) have both heavily criticised South Africa for even daring to attempt to intervene in Zimbabwe, saying that Harare was not “a backyard” or “province” of South Africa. The presidential spokesperson went as far as suggesting that South Africa only achieved independence in 1994 and was therefore “too young” to intervene in Zimbabwe.

However, according to Wits University’s Professor Mills Soko, “given Zimbabwe’s overwhelming dependence on South Africa, it still has the political, diplomatic and economic power to shape an inclusive, peaceful and progressive long-term political settlement in the country”.

It should be clear now that South Africa’s policy towards Zimbabwe is ineffective and simply does not work against Zanu-PF. The brazenly intransigent regime in Harare will not be moved by a policy which fails to recognise the true political nature of the Zimbabwe crisis. Without asserting it’s significant leverage to rein in the Zimbabwean government, South Africa is increasingly being viewed as insincere, incapable, or both.

Soko argues that perhaps the most important factor affecting any meaningful interventionist policy in Zimbabwe is the tag of being former liberation war parties:

“For several years, the ANC government’s engagement with Zimbabwe has been guided by the nebulous notion of liberation solidarity between the ANC and Zanu-PF, not by the national interests outlined in South African foreign policy.”

This seems to virtually incapacitate the ANCs ability to rein in its counterpart.

Ministers Naledi Pandour, Lindiwe Zulu and others have been vocal in describing the situation in Zimbabwe as a “crisis”. However, they cannot be expected to do much individually if there is no political will or capability at the highest levels of the state, government and region.

Conclusion

Despite all the challenges of intervening in the domestic affairs of a sovereign state, which refuses to accept the necessity, nay, legitimacy of such well-meaning intervention, South Africa has a strong interest and obligation in taking a more decisive position on Zimbabwe. As Elizabeth Sidiropolous, the CEO of the South African Institute of International Affairs, observed, the fate of the neighbouring state has a profound influence on the economy of the entire region.

For about 20 years, South Africa has watched, rarely exerted pressure and in some instances aided and abetted the tragedy Zimbabwe has become.

But that must change. Now President Ramaphosa and South Africa need to appreciate the enormous potential they have to help restore Zimbabwe economically and politically. The criticisms coming from Harare should not dissuade the regional power from pursuing a more pragmatic approach that will force the authorities in Zimbabwe to pause and begin taking their governance and human rights mandate seriously. DM/MC

The Southern Africa Human Rights Roundup is a weekly column aimed at highlighting important human rights news in southern Africa. It integrates efforts of human rights defenders and facilitates evidence-based engagement with key stakeholders and institutions on the human rights situation across the region.

The roundup is a collaboration between the Southern Africa Human Rights Defenders Network and Maverick Citizen.