Last February, the legal research company Casetext launched Compose, a first-of-its-kind product that uses artificial intelligence to help create the first draft of a litigation brief in a fraction of the time it would normally take.

At the time, as I wrote in this February blog post, cofounder and CEO Jake Heller said the product was “poised to disrupt the $437 billion legal services industry and fundamentally change our understanding of what types of professional work are uniquely human.”

While the product initially covered a limited set of core motions related to federal civil procedure and discovery, Casetext said it would roll out other motion collections over time for specific areas of law.

Today Casetext is introducing the first of those new collections — a set of 18 employment law briefs — 16 related to wage and hour cases in federal courts as well as under state law in California and New York, and two Title VII motions that are a preview of a forthcoming larger set of employment discrimination briefs.

This initial employment law collection will eventually be expanded to include two briefs relating to defending against Title VII claims.

The set of wage-and-hour briefs released today cover motions in federal courts to:

- Compel discovery.

- Seek conditional certification.

- Certify a class.

- Decertify a class action.

- Request summary judgment.

- Compel arbitration (applying general contract law principles).

- Compel arbitration (applying California law).

- Compel arbitration (applying New York law).

In addition, for wage-and-hour cases under both California and New York law, the collection includes briefs in support of motions to:

- Compel discovery.

- Certify a class.

- Seek summary judgment.

- Compel arbitration in California state court (applying both federal and California law).

- Compel arbitration in New York state court (applying both federal and New York law).

The two Title VII briefs for for motions to dismiss and for summary judgment.

Draft A Brief in Five Minutes

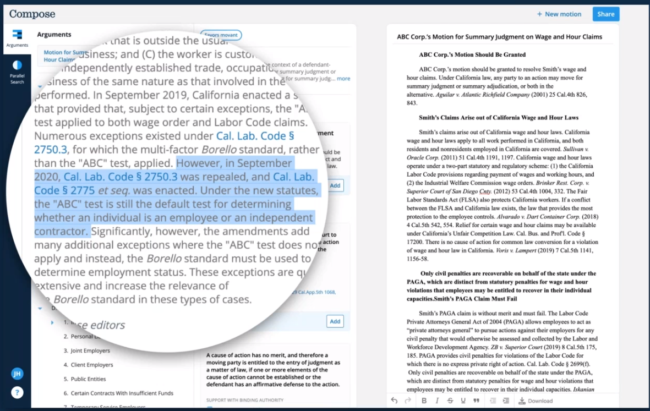

During a media preview on Tuesday, Heller demonstrated how he could use Compose to draft a brief in support of a motion for summary judgment in five minutes.

As I explained in my February post about Compose, the drafting process begins by selecting the type of motion, the court, the parties, and the position to be taken by the party you represent, for or against the motion.

You are then presented with a treatise-like list of all the available arguments for that motion. As you choose an argument, Compose then shows you the legal standards and rules applicable to that argument. As you see these standards displayed, you simply click Add and it shows up in the draft brief on the right side of your screen.

The lawyer continues this process, perusing the available arguments and standards, and then clicking Add to add a fully composed paragraph to the brief that states the rule, including citations. The text is fully editable, either within Compose or later when the draft is exported to Word.

“Picking arguments to add to your brief is like choosing pastries at a French patisserie,” Heller said when he first demonstrated this product during Legalweek last February.

In Heller’s demonstration Tuesday, it actually took him about eight minutes to draft the brief, but I doubt many lawyers would complain about an extra couple of minutes. And while Compose can be used to produce a fairly substantive draft, it is not a finished product ready for filing. You still need to draft the statement of the case, the facts, and other sections, tie it all together, and put it into the correct format.

More Coverage than A Treatise

Casetext says that its wage-and-hour collection for Compose is comprehensive in its coverage. During Tuesday’s demonstration, cofounder Laura Safdie said that the collection includes:

- 1,102 arguments.

- 5,354 legal standards.

- 25,236 citations.

By comparison, Safdie said that they analyzed a major treatise covering wage-and-hour cases and found that it had just 248 citations in the section related to summary judgment motions. Compose has over 3,000 citations for those motions, she said.

The Secret Sauce

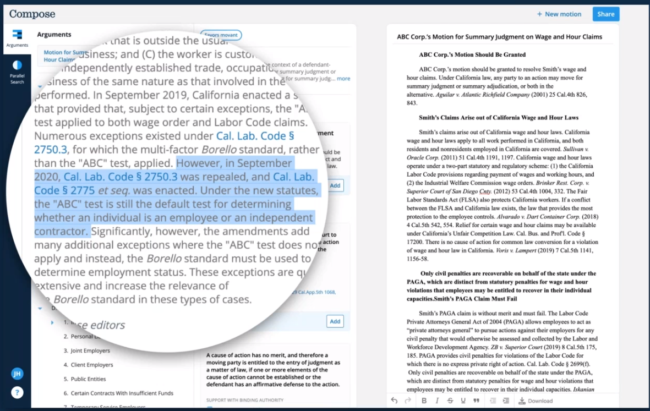

If this were the entirety of Compose, it would be impressive technology. But Compose includes an additional feature, driven by artificial intelligence, called Parallel Search, that makes it even more impressive — and more useful when actually drafting a brief.

Parallel Search uses advanced natural language processing to follow you as you draft your arguments in the brief and then automatically provide you conceptually relevant precedent. Notably, Casetext says this works to find analogous caselaw, even when the cases do not use the same language.

In Heller’s brief-drafting demonstration on Tuesday, he pretended he was representing drug manufacturer Pfizer in a lawsuit brought by a salesperson working as an independent contractor. Using Parallel Search to draft his arguments, he wrote the statement:

“Pfizer’s salespeople work independently and sell on their own, and so are not employees covered under the FLSA.”

Parallel Search then provided cases to support that statement. Although that sentence never identified Pfizer as a pharmaceutical company, Parallel Search understood to deliver cases related to the pharma industry, and it also knew to deliver cases related to an FLSA exemption for outside sales people.

During Tuesday’s demonstration, Javed Qadrud-Din, Casetext’s director of machine learning, said that Parallel Search grew out of Casetext’s own need, in developing Compose, to have a search tool that could find support for legal propositions, even when courts used completely different language.

An example of Parallel Search’s ability to understand concepts.

He offered several examples of how this transformer-based neural network is able to learn to understand words and sentences in context. For example, this statement was entered into Parallel Search:

“Target’s employees were uncompensated while waiting for loss prevention inspections before leaving work.”

It returned the following statement from the case Frlekin v. Apple Inc. (9th Cir. 2020):

“Employees receive no compensation for the time spent waiting for and undergoing exit searches, because they must clock out before undergoing a search.”

Thus, Parallel Search understood that “uncompensated” was the same as “no compensation,” that “loss prevention inspections” were similar to “exit searches,” and that “before leaving work” was similar to “must clock out.”

What It Costs

Casetext sells Compose as a separate product from its legal research service. For now, it is offering free trial access to Compose for anyone who requests an account.

In general, Casetext sells Compose to larger firms on a subscription basis. Firms can subscribe to Compose in its entirety or just to specific collections. Casetext did not provide specific pricing.

When Casetext launched Compose in February, it offered special pricing for solo and small-firm attorneys by which they could purchase access on an a-la-carte basis.

A spokesperson said the company is currently rethinking its pricing for smaller firms to make Compose more accessible.

The Bottom Line

In a study it released in July, Casetext said that compose allows litigators to draft briefs 76% faster than they otherwise would.

Insofar as the study involved only 13 lawyers and relied on their estimates of the time it would normally take them to write a brief, it was not exactly scientific.

But what cannot be doubted about Compose is that it enables lawyers to create a first draft in substantially less time than they would otherwise require.

Not only that, but it provides lawyers a high degree of assurance that they have at least considered all the arguments available to them, regardless of whether they choose to use them.

This argument reflected a legislative amendment from this month.

This argument reflected a legislative amendment from this month.

Further, Casetext says the arguments in Compose are kept current with changes in the law. In an example shown by Safdie Tuesday, an argument reflected a September amendment of a California statute.

Something Heller said back in February still resonates today:

“Compose commoditizes the parts that lawyers never liked working on and clients never liked paying for. At the end of the day, what’s left is the lawyer’s imagination, creativity, intelligence and persuasiveness in the brief-drafting process.”

Casetext calls Compose a game-changer, and this may be one of the few times in the annals of marketing where that is not an exaggeration. If you are a litigator, try it for yourself. It won’t cost you anything. And if you are an employment litigator, you now have even more reason to try Compose.

Staci Zaretsky is a senior editor at Above the Law, where she’s worked since 2011. She’d love to hear from you, so please feel free to email her with any tips, questions, comments, or critiques. You can follow her on Twitter or connect with her on LinkedIn.

Staci Zaretsky is a senior editor at Above the Law, where she’s worked since 2011. She’d love to hear from you, so please feel free to email her with any tips, questions, comments, or critiques. You can follow her on Twitter or connect with her on LinkedIn.

Kathryn Rubino is a Senior Editor at Above the Law, and host of

Kathryn Rubino is a Senior Editor at Above the Law, and host of

Jordan Rothman is a partner of

Jordan Rothman is a partner of

This argument reflected a legislative amendment from this month.

This argument reflected a legislative amendment from this month.

Jill Switzer has been an active member of the State Bar of California for over 40 years. She remembers practicing law in a kinder, gentler time. She’s had a diverse legal career, including stints as a deputy district attorney, a solo practice, and several senior in-house gigs. She now mediates full-time, which gives her the opportunity to see dinosaurs, millennials, and those in-between interact — it’s not always civil. You can reach her by email at

Jill Switzer has been an active member of the State Bar of California for over 40 years. She remembers practicing law in a kinder, gentler time. She’s had a diverse legal career, including stints as a deputy district attorney, a solo practice, and several senior in-house gigs. She now mediates full-time, which gives her the opportunity to see dinosaurs, millennials, and those in-between interact — it’s not always civil. You can reach her by email at