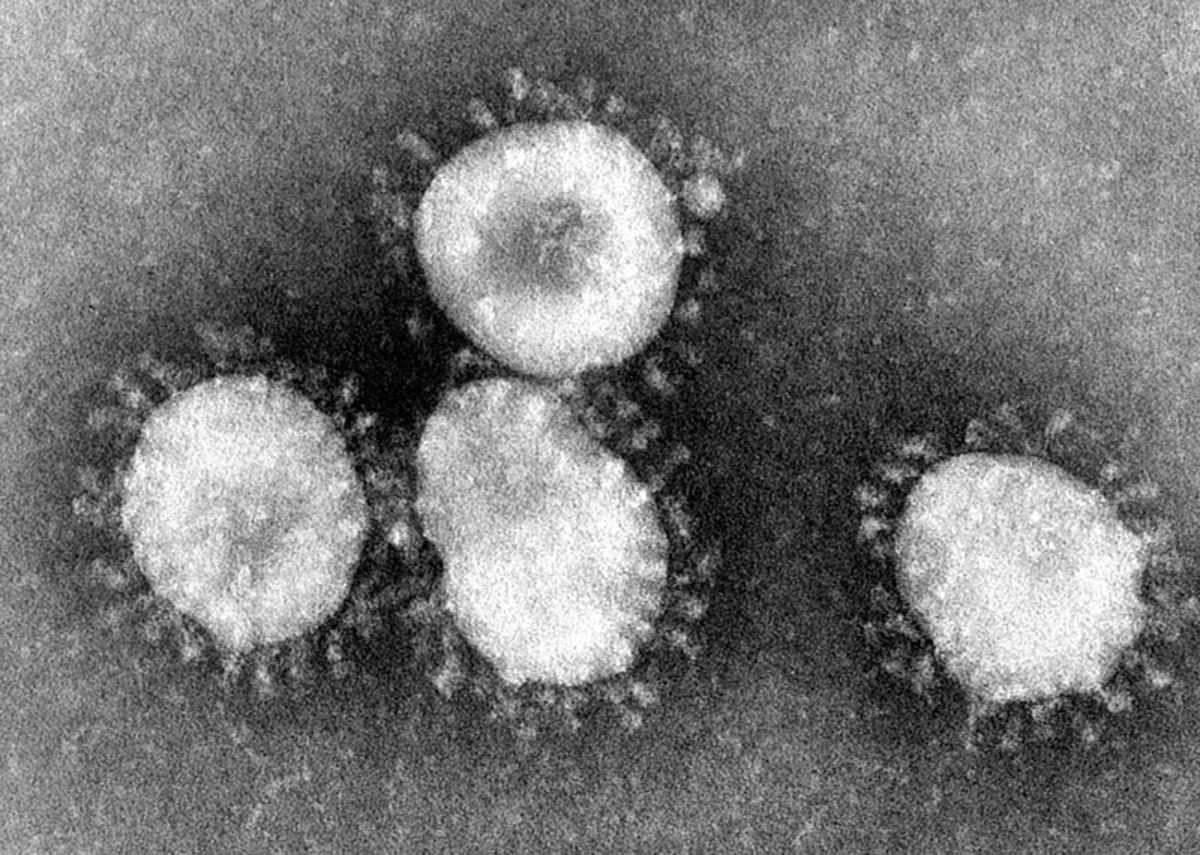

For lawyers, things just aren’t what they used to be. A lot has changed over the past 20 years, and the pandemic has only accelerated the pace of change. Between mobile phones, cloud-based legal software, and artificial intelligence, the tools that lawyers use to get the job done look very different than they did at the turn of the century.

One of the primary areas where technology first affected the day-to-day practice of law was legal research. When I graduated from law school in 1995, we were just beginning to use CD-ROMS (remember those?) to conduct legal research. Within a few years, legal research transitioned to online, and lawyers were able to conduct research from any computer, whether at work or at home.

From there, advances in legal research came steadily, but slowly — until about five years ago. That’s when artificial intelligence tools, such as data analytics and natural language processing, became increasingly common and were soon incorporated into legal research tools. Those advances greatly improved legal research, but arguably increased its complexity, since so many different platforms and legal research tools, both free and fee-based, are now available to lawyers.

That’s where “A Short & Happy Guide to Advanced Legal Research,” authored by Ann Walsh Lang comes in. When I received my complimentary copy of this book for review purposes, I quickly discovered that it’s exactly what the title suggests: a “how to” of legal research that provides an overview of the vast array of legal research tools available to litigators at each stage of a case.

Two stand-out features of this book are the breadth of coverage and its format. It includes information about a variety of free online tools, including public records databases, newsletters, and encyclopedias, and case law and statutes. Also covered in depth are a vast assortment of fee-based legal research tools, ranging from more traditional case law and statutory research tools to cutting edge AI-based legal research and data analytics software.

The way in which this information is provided is part of what makes this book so useful. First, there’s the format of each chapter. As explained in the introduction, different firms have different needs — and resources — and the structure of each chapter reflects that reality:

Like so many things in life, legal research requires choices. When you have more time than money, you can look for good and cheap resources. When you have more money than time you can look for good and fast resources. The resources I discuss in this book are all good, but many are not cheap. In each chapter, I will provide a comparison chart of good, cheap, and fast resources. When a resource is cheap, it is free or low-cost. When a resource is fast, it is available online from your desktop or provides a comparably huge savings in time.

Also significant is the way that the book is organized. The first and last two chapters address: 1) the top five questions to ask before beginning legal research, 2) the ethics of online legal research, and 3) upper-level writing legal research. The remaining chapters are each focused on the different stages of a case, the questions you’ll need to ask during that phase of the case, and the legal research resources available that could prove useful in answering those questions:

- Chapter 2. Litigation Phase I: Case Assessment Part 1: Is There a Valid Cause of Action?

- Chapter 3. Litigation Phase I: Case Assessment Part 2: Is the Issue Worth Pursuing?

- Chapter 4. Litigation Phase II: Discovery and Investigation

- Chapter 5. Litigation Phase III: Pretrial Action Finding Pleadings, Motions, and Briefs

Another notable aspect of this book is its up-to-date coverage of AI-based legal research tools. In the relevant chapters, applicable AI software programs are covered, with a discussion of the functionality of the software and why it’s useful in that context. The AI legal research tools discussed include:

- Fastcase’s Docket Alarm and Analytics Workbench

- Lexis Advance Litigation Profile Suite and Lex Machina

- Westlaw Edge Litigation Analytics

- Bloomberg Law Trackers

- LexisNexis Context

- Westlaw Profiler and Thomson Reuters Expert Witness Service

- Bloomberg Law Litigation Analytics

- Casetext CARA

- Judicata’s Clerk

So whether you’re a seasoned attorney who needs to brush up on the latest legal research tools or a law student just starting out, there’s something in this book for everyone. Legal research is in the midst of a new wave of change, in large part driven by AI software, so why not get in front of it by investing in this book? At just $22, you’ve got very little to lose and lots to gain!

Nicole Black is a Rochester, New York attorney and Director of Business and Community Relations at MyCase, web-based law practice management software. She’s been blogging since 2005, has written a weekly column for the Daily Record since 2007, is the author of Cloud Computing for Lawyers, co-authors Social Media for Lawyers: the Next Frontier, and co-authors Criminal Law in New York. She’s easily distracted by the potential of bright and shiny tech gadgets, along with good food and wine. You can follow her on Twitter at @nikiblack and she can be reached at niki.black@mycase.com.

Jill Switzer has been an active member of the State Bar of California for over 40 years. She remembers practicing law in a kinder, gentler time. She’s had a diverse legal career, including stints as a deputy district attorney, a solo practice, and several senior in-house gigs. She now mediates full-time, which gives her the opportunity to see dinosaurs, millennials, and those in-between interact — it’s not always civil. You can reach her by email at

Jill Switzer has been an active member of the State Bar of California for over 40 years. She remembers practicing law in a kinder, gentler time. She’s had a diverse legal career, including stints as a deputy district attorney, a solo practice, and several senior in-house gigs. She now mediates full-time, which gives her the opportunity to see dinosaurs, millennials, and those in-between interact — it’s not always civil. You can reach her by email at

Jordan Rothman is a partner of

Jordan Rothman is a partner of