There is no dispute about the depths of political, ethical and economic degradation of Zimbabwe after two and a half years of Emmerson Mnangagwa’s Presidency.

No dispute because his own ministers and advisors publicly admit the state is on the brink of collapse due mainly to the grand corruption of the country’s ruling class.

Worse still for Mnangagwa, many junior officers share the view that he and the predatory elite that he leads are steering the country into the abyss.

It is this message from the junior officers and the ranks of the military that is unsettling the generals, with whom Mnangagwa has shared the spoils of state capture. Although Mnangagwa and his deputy General Constantino Chiwenga were once seen as inseparable allies, the looming failure of the Zimbabwean state is sharpening the elite’s sectional and divergent interests.

By allowing corruption to rip through the system, from illegal gold and diamond exports to arbitrage between the US dollar and the latest version of Zimbabwe’s currency, Mnangagwa has undermined his own praetorian guard.

Hollowed out and looted, the state can no longer look after its own soldiers and police, and their families – let alone address the spectre of mass starvation and a public health emergency haunting over half of Zimbabwe’s 16 million people.

Finance Minister Mthuli Ncube wrote to the IMF last month lamenting that the “…economy could contract by 15-20% during 2020 with very serious social consequences. Already 8.5 million Zimbabweans (half the population) are food insecure.”

So bad is the situation, wrote Ncube, that Zimbabwe’s state could implode and threaten security in neighbouring states. He warns: “… the global pandemic will take a heavy toll on the health sector with many lives lost and raise poverty to levels not seen in recent times, including worsening food security.”

This ranks as a tragic admission of political defeat.

Mnangagwa and his military allies insisted they had organised the overthrow of Robert Mugabe in 2017 to stamp out corruption, to open the country for business and hold free and fair elections. On their own admission they have failed.

Listen to Shingi Munyeza, a kingpin of Zimbabwe’s business class and an member of Mnangagwa’s advisory couincil, describe how the government is leading Zimbabwe into perdition:

“These are the last kicks of a dying horse, of a system that is evil and corrupt… our state is captured by cartels who are operating with those who are in power, strong men, to the detriment of the rest of us,” says Munyeza in a remarkable indictment of a government with which he had worked closely.

“They move from state capture to state abuse where citizens are being abused, physically, emotionally …. there is nothing that passes on to the ordinary man or ordinary woman and then it moves on to state failure which I believe is where we are heading now…”

A senior pastor in the Faith Ministries Church as well as a wealthy businessman, Munyeza is now prophesying the fall of Mnangagwa’s government, relayed over social media. It resonates strongly with the military, some of whose top officers are said to be backing him.

Why sound the alarm bells now after years of elite plunder of Zimbabwe? Some, at least, in the predatory elite are seriously rattled by the prospect of state collapse and their own survival in a new order.

Last year’s revolution in Sudan offers several parallels. A grassroots movement, outside the confines of traditional opposition parties, brought together trades unionists, professionals and community activists across the country, building from street level in the regions until it became an unstoppable national force.

Under the ousted Omar Al-Bashir regime, Sudan’s deep security state, with its myriad militias and spy networks, electronic surveillance and capacity to wage civil wars in four regions simultaneously was a still more formidable apparatus than Zimbabwe’s Central Intelligence Organisation and its many proxies.

Yet it was the combination of Sudan’s economy going into free fall – mass demonstrations were triggered by a threefold increase in the price of bread – and deepening schisms between rival wings of the security state that opened the avenue for its revolutionaries to race on to the national stage and force out the political leadership.

If anything economic conditions in Zimbabwe are currently worse than those in Sudan under Al Bashir. At least Sudan’s regime had some regional sponsors such as Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates. Mnangagwa’s government evinces no regional solidarity.

South Africa, whose ministers worry about the worsening instability and grand corruption north of the Limpopo, makes ritualistic complaints about the unfairness of sanctions which bar Zimbabwe from borrowing from the IMF.

In truth, President Cyril Ramaphosa is exercised about Harare’s debt mountain with South Africa and a growing tide of Zimbabweans heading south to compete on the local labour market.

At home in Zimbabwe, the continuous profiteering and nepotism in the award of state contracts as half the country face what the UN euphemistically calls ‘food insecurity’ tells people that the Mnangagwa government ha plumbed new moral depths. Some of his oldest allies now fear popular retribution, and that they cannot rely on the fracturing security services to protect them.

Activists, journalists and opposition politicians who point out this demeaning of our country under Mnangagwa’s rule are beaten, tortured and killed. As the European colonialists found out, Zimbabweans are slow to anger but when they decide to fight, they become an implacable force.

Mnangagwa and his allies are about to discover that again as they are held to account for the destruction of our country and the theft of our futures.

Mnangagwa did the exact opposite of fighting corruption. The government reinforced a system of primitive accumulation in which a narrow predatory elite of which he is patron, benefits from corrupt state contracts and tenders.

Economic policy is used to benefit his Mnangagwa’s business cronies such as Kudakwashe Tagwirei and his Sakunda Fuels. Tagwirei made so much money from Sakunda’s monopolistic position as a supplier of fuel and farm inputs for the state-sponsored Command Agriculture programme that it was able to finance Mnangagwa’s and ZANU-PF’s election campaign in July 2018.

Now Mnangagwa’s regime is repaying Tagwirei, ensuring the central bank offers him opportunities for arbitrage and money laundering opportunities. Former Finance Minister Tendai Biti, an opposition who chairs the Public Accounts Committee in parliament, told parliament that the government

Mnangagwa, aided by finance minister Ncube and Beserve Bank governor John Mangudya, have tipped the country back into the economic abyss of 2008 – mass unemployment and hunger, hyper-inflation and a worthless national currency.

They facilitated the grand theft of citizens’ bank balances by reintroducing the Zimbabwean dollar currency while allowing their business allies to access to the state’s reserves of US dollars, and to benefit from the arbitrage between the two currencies. This corruption system built around the relaunch of the Zimbabwean dollar, which cost our people US$500 million in stolen state resources, guaranteed the new currency was strangled at birth.

By late May, Mangudya claimed an official exchange rate of Zim$25=US$1 – in reality it was taking pover Z$70 to buy a US dollar, and the rate has been falling daily. Inflation has skyrocketed to at least 700%, second only to Venezuela.

So far Mnangagwa seems impervious to the consequences of this economic incontinence, seeing no need to rein in his extravagances. He has been renting luxury jets from as far as the United Arab Emirates to take him on 400 kilometre trip within Zimbabwe.

He has appointed several ministers known to be corrupt. His top appointees have looted over $300m from the citizens pension fund with no official inquiries , let alone prosecutions.

As a smokescreen, he appointed a presidential anti-corruption team that delivered nothing whilst his reconstituted Zimbabwe Anti-Corruption Commission acquired the ‘catch and release’ moniker.

Mnangagwa’s officials have failed to account for US$3b Command Agriculture budget, much of which enriched ruling party cronies such as Tagwirei.

By using the COVID-19 crisis to issue a fiat banning public passenger transport companies, Mnangagwa cleared the decks for the government and Tagwirei-controlled Zimbabwe United Passenger Company for further profiteering via inflated procurement contracts.

Despite hiring lobbyists in Washington DC, international views of the Mnangagwa government are overwhelmingly negative. Almost none of the promised US$10bn in foreign investment has materialised.

Salaries are worth just a fraction of what they were when Mnangagwa seized power. When doctors, nurses, teachers and others protest against these rock bottom wages and working conditions, the government unleashes the police to break up demonstrations. Sometimes, its agencies send thugs to abduct union leaders and oppositionists, who are tortured and left for dead on the outskirts of Harare.

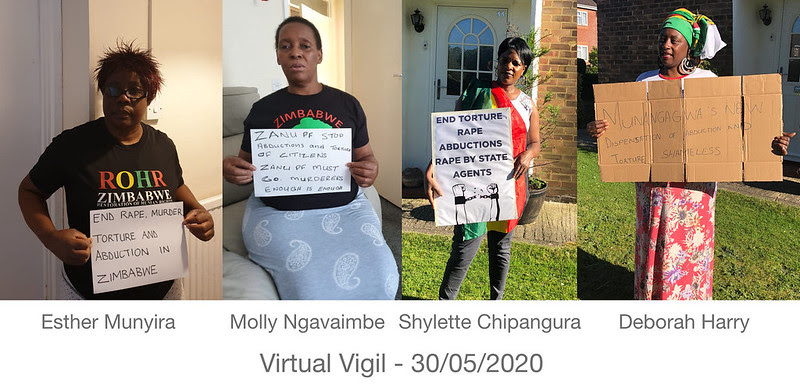

In the latest atrocity state security agents abducted three women from the youth league of the Movement for Democratic Change, to torture and sexually abuse them for almost two days before pushing them out of a moving car about 90km from Harare.

In January 2019, Mnangagwa sent the army to quell protests against higher fuel prices. He later boasted that he had told the army to “use a whip laced with salt” against the dissidents.

Political repression has ramped up as the state’s utilities fall apart. Power cuts drag on for days, even weeks. Clean running water is a scarcity in many towns.

Doctors and nurses are struggling to improve pay and conditions. Fearing a breakdown of the public health service, Econet chief executive Strive Masiyiwa contributed to their salary funds.

COVID-19 salt to the wound

When the COVID-19 pandemic broke out in Asia, predictions of its consequences in Zimbabwe were dire.

Despite advance warnings, the government was dismissive of the threat. The Defence Minister suggested that COVID-19 was divine punishment against th US for imposing sanctions on Zimbabwe.

Led by an incompetent and unqualified Health Minister, Obadiah Moyo, whom Mnangagwa has retained despite multiple epic failures, the country lacked any strategy for COVID-19.

It relied on testing kits donated by Chinese billionaire Jack Ma but failed to distribute these in time.

COVID-19 saw health workers unprepared and unprotected, health infrastructure for infectious diseases non-existent and treatment facilities and equipment unavailable.

The largest burden of mobilising support for COVID-19 response has been borne by citizens, coming together to raise funds for personal protective equipment for health workers, sanitisers, and the refurbishment of isolation facilities.

The pandemic has exposed shocking levels of elite self-interest with reports of preferential treatment for the first reported case, Zororo Makamba, son of former Zanu PF Member of Parliament, James Makamba, who later died.

This would be followed by reports of establishment of private COVID-19 treatment facilities for the elite and its families by Tagwirei.

A young boy sits in a queue for cooking gas in Harare, Zimbabwe, Sunday, March, 29, 2020. Zimbabwean President Emmerson Mnangagwa announced a nationwide lockdown for 21 days, starting March 30, in an effort to stop the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic. (AP Photo/Tsvangirayi Mukwazhi)

Ignoring the difficulties that the globally recommended lockdown protocols would present in Zimbabwe, the government saw the restrictions as a way of stifling social dissent.

Mnangagwa is trying to use COVID-19 to entrench his authoritarian rule, passing regulations that stifle free speech, arresting journalists, deploying police and soldiers to violently enforce the lock down, using the lockdown to decimate the opposition and unleashing state agents to abduct, torture and sexually abuse activists.

Fearing that the combined impact of food shortages, economic crises and political contagion would trigger a public backlash against his government, Mnangagwa has extended the COVID-19 lockdown indefinitely. His decision lacks any scientific justification and rationality.

#ZanuMustGo

Two and half years after the coup, and two years after the disputed election, there is consensus at least that Mnangagwa has failed.

Internal rivalries inside Zanu PF are an open secret with new factions that pit Mnangagwa against his Deputy Constantine Chiwenga.

The public spats between his close ally and former deputy information minister Energy Mutodi and his boss Monica Mutsvangwa and Foreign Minister, former army General Sibusiso Moyo – one of the leading actors in the coup- suggest that the fallout is more serious than Zanu PF is willing to admit.

Most important is the shift among Zimbabweans who can no longer tolerate the Mnangagwa-Zanu PF regime and see no prospect for its reform. Its combination of grand corruption, serial incompetence and brutal repression are beyond redemption.

Making matters still worse is the pomposity, arrogance and epic hypocrisy of the ruling elite, founded on their belief that they can always bludgeon their way out of trouble, thanks to the blind loyalty of Zimbabwean soldiers and police. A reality check on that front is about to confront Mnangagwa and his allies head on.

A brief tour of Africa would prove informative for them. In Malawi, after years of apparent docility, a citizens’ movement emerged to reject the fixed outcome and demand fresh election after elections were manipulated by President Peter wa Mutharika.

The movement successfully defied, violence, killings and intimidation and endured for over a year culminating in an independent adjudication of the electoral petition by the courts and a decree to nullify the election and order a fresh poll.

In Tunisia, in 2010, although living conditions were comparatively better than Zimbabwe’s, a self-immolation by a street vendor, triggered a 28-day public protestsa 28-day public protest and what became the Jasmine Revolution that ousted president Zine El Ben Al I after 24 years in power.

In Egypt, in 2011, crash living conditions and an oppressive governance system triggered public protests that culminated with demands for President Hosni Mubarak’s resignation.

In Burkina Faso, in 2014, attempts by former President Blaise Campaore to extend his 27-year term in office triggeredoffice triggered countrywide protests that culminated in his resignation.

More recently in 2019, an attempt by Algerian President Abdelaziz Bouteflika to seek a fifth term in office, triggered successful public protests to demandi his resignation and radical changes in the political system.

What all these change in regimes have in common is that they were achieved by popular movements, not established opposition parties. There is a vital lesson here for the country’s fractious opposition parties – if they fail to come together as a serious national movement demanding political change, they will be sidelined.

For rival politicians in the MDC to be fighting on court over political minutiae at a time of unprecedented human suffering is chipping at their street credibility. So too is the record of many local authorities under MDC control: their theft of public resources looks like a poor man’s imitation of Zanu-PF’s grand corruption in central government.

Just a matter of time

This shift by citizens from national political consciousness and then to action is not easy and direct. But it is now a matter of when not if.

And when the popular protests reach their peak, experience has shown that it will not matter whether Mnangagwa has the backing of the army commanders. Other revolutions have succeeded against repressive regimes with still stronger armies. The writing is on the wall.