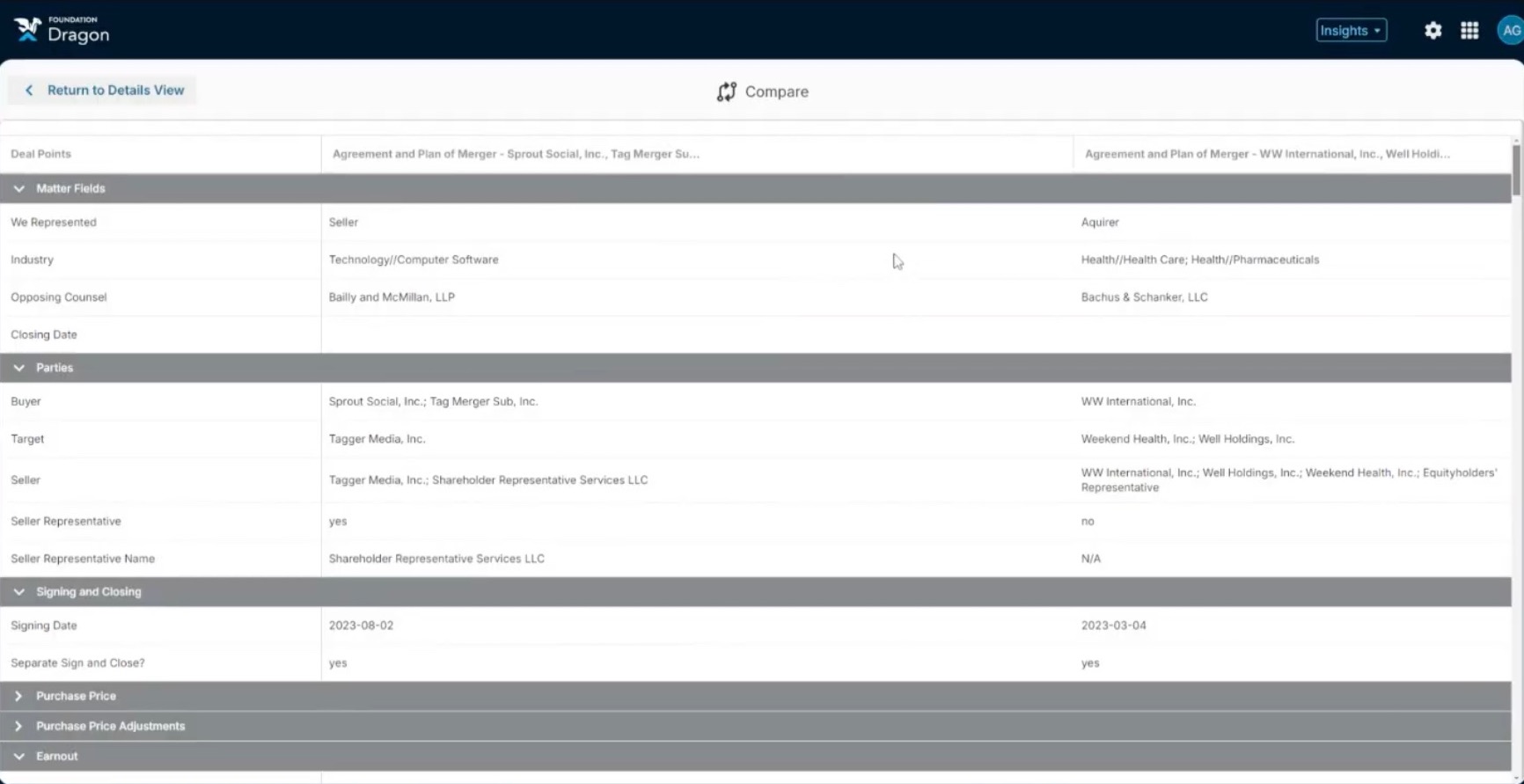

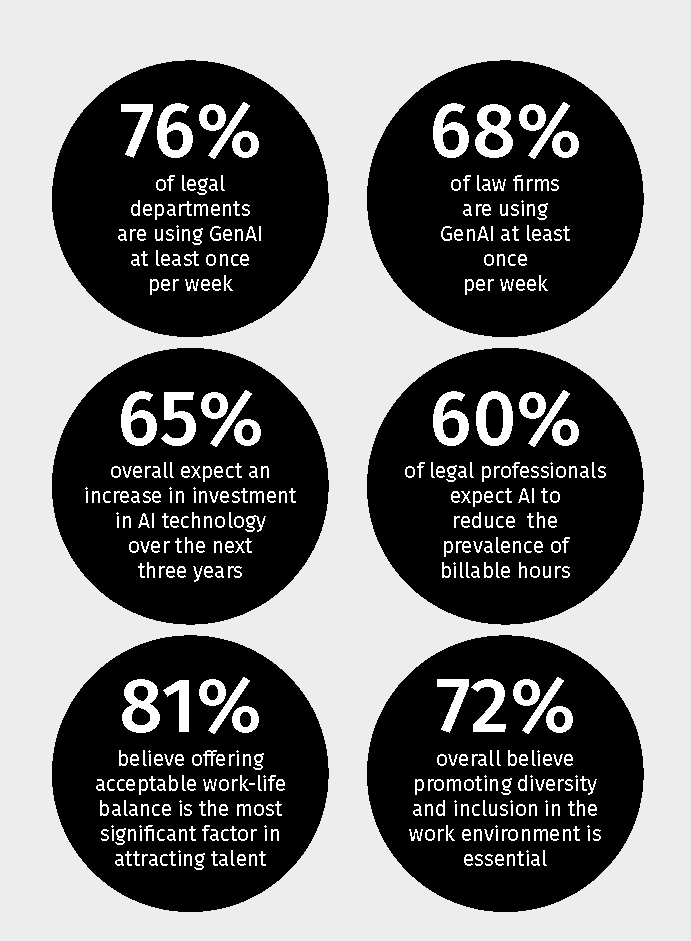

Seventy-six

percent

of

legal

professionals

in

corporate

legal

departments

and

68%

in

law

firms

are

using

generative

AI

at

least

once

a

week,

with

a

third

of

those

professionals

using

it

daily.

That

is

among

the

findings

of

the

2024

Future

Ready

Lawyer

Survey

from

Wolters

Kluwer,

the

sixth

edition

of

a

report

that

offers

an

annual

view

of

the

legal

industry’s

evolving

landscape,

with

a

particular

emphasis

on

technology,

especially

generative

AI,

and

how

these

advancements

are

reshaping

law

firms

and

corporate

legal

departments.

Based

on

responses

from

712

legal

professionals

in

10

countries,

the

report

outlines

significant

trends,

challenges,

and

opportunities

the

industry

is

facing

over

the

next

three

years.

These

include

technology

integration,

evolving

client

expectations,

talent

management,

environmental,

social,

and

governance

(ESG)

considerations,

and

information

security.

Gen

AI

Adoption

Not

surprisingly,

the

report

finds

that

the

integration

of

gen

AI

is

one

of

the

most

significant

trends

in

the

legal

industry,

offering

the

potential

to

streamline

processes,

improve

efficiency,

and

reduce

manual

tasks.

Increasingly,

the

legal

industry

is

adopting

gen

AI

to

handle

routine

legal

processes,

such

as

legal

research,

document

review,

and

drafting.

This

shift

allows

legal

professionals

to

focus

on

more

complex,

value-added

tasks,

the

report

says.

According

to

the

report,

76%

of

legal

professionals

in

corporate

legal

departments

use

gen

AI

at

least

once

a

week,

compared

to

68%

of

those

in

law

firms.

A

third

of

respondents

use

it

daily.

In

addition,

65%

of

legal

professionals

expect

AI

technology

investment

to

increase

over

the

next

three

years.

But

despite

all

the

enthusiasm

around

gen

AI,

many

challenges

remain,

the

report

says.

Among

the

challenges

most

frequently

cited

by

respondents

were

issues

related

to

integration,

trust

in

AI-generated

outcomes,

and

concerns

over

ethics

and

data

privacy.

Integrating

gen

AI

into

existing

legal

systems

and

workflows

remains

difficult,

the

survey

says,

with

37%

of

respondents

in

law

firms

and

42%

in

corporate

legal

departments

citing

this

as

a

significant

challenge.

Two

other

major

issues

are

concerns

over

the

accuracy

of

gen

AI

outputs

and

the

ethical

implications

of

using

AI

in

legal

work.

Around

41%

of

law

firm

professionals

and

37%

of

corporate

legal

professionals

expressed

doubts

about

the

reliability

of

gen

AI

results.

Despite

these

challenges,

the

report

underscores

that

gen

AI

is

no

longer

an

optional

tool

but

a

necessary

component

for

future-ready

legal

organizations.

To

fully

leverage

the

benefits

of

gen

AI,

legal

professionals

will

need

ongoing

training,

ethical

guidelines,

and

robust

review

processes

to

mitigate

issues

like

AI

“hallucinations.”

AI’s

Impact

on

the

Billable

Hour

Gen

AI’s

ability

to

drive

efficiency

is

expected

to

have

a

profound

impact

on

traditional

legal

business

models,

particularly

the

reliance

on

billable

hours,

the

report

concludes.

The

reliance

on

billable

hours,

once

a

staple

of

the

legal

profession,

is

expected

to

decline

as

law

firms

adopt

new

pricing

models,

such

as

flat

fees

and

value-based

billing.

It

finds

that,

overall,

60%

of

legal

professionals

expect

AI

to

reduce

the

dominance

of

the

billable

hour

model,

with

67%

of

corporate

legal

departments

and

55%

of

law

firms

believing

that

AI-driven

efficiencies

will

significantly

impact

the

prevalence

of

the

billable

hour.

More

than

half

of

the

respondents

feel

prepared

to

adapt

their

business

practices,

workflows,

and

pricing

models

to

accommodate

these

changes.

Attracting

and

Retaining

Talent

On

another

topic,

the

report

finds

at

attracting

and

retaining

top

legal

talent

remains

a

challenge

in

an

industry

undergoing

transformation.

In

particular,

legal

professionals

emphasized

the

value

of

work-life

balance,

competitive

compensation,

and

opportunities

for

continuous

learning.

The

report

says

that

81%

of

respondents

emphasized

the

importance

of

work-life

balance,

and

82%

believed

their

organization

performed

well

in

this

area.

And,

in

an

age

when

AI

is

becoming

more

integrated

into

legal

work,

72%

of

respondents

stated

that

technological

proficiency

is

increasingly

essential

when

hiring

new

talent.

ESG

Issues

There

continues

to

be

growing

demand

for

expertise

in

environmental,

social,

and

governance

(ESG)

issues,

and

that

demand

is

putting

pressure

on

both

corporate

legal

departments

and

law

firms,

the

survey

finds.

That

said,

corporate

legal

departments

feel

better

prepared

to

address

ESG

demands

than

law

firms,

with

41%

of

corporate

respondents

feeling

“very

prepared”

compared

to

only

29%

of

law

firm

respondents.

However,

both

sectors

face

challenges,

particularly

in

terms

of

training

staff

and

aligning

with

regulatory

changes.

While

the

need

for

ESG

training

is

clear,

the

report

says,

less

than

half

of

law

firms

currently

offer

such

programs.

Among

corporate

legal

departments,

56%

offer

ESG

training.

The

report

cautions

that,

as

ESG-related

demands

grow,

firms

that

fail

to

adapt

may

struggle

to

meet

client

expectations.

The

Challenge

of

Information

Security

Another

challenge

faced

by

respondents

in

the

survey

is

information

security.

With

the

rise

of

cyberattacks

and

data

breaches,

74%

of

legal

professionals

see

escalating

information

security

challenges

as

a

major

trend,

with

33%

expecting

a

significant

impact

on

their

organization.

However,

only

29%

of

respondents

feel

“very

prepared”

to

meet

these

security

challenges,

despite

80%

believing

that

their

organization

is

generally

prepared.

This

gap

between

general

readiness

and

complete

preparedness

underscores

the

need

for

ongoing

improvements

in

information

security

practices.

“The

question

of

whether

legal

professionals

are

future-ready

remains

relevant

and

compelling,

even

after

six

years

of

Future

Ready

Lawyer

research,”

the

report

concludes.

Clearly

that

is

so,

as

the

survey

paints

a

picture

of

an

industry

in

the

midst

of

profound

transformation,

due

most

strikingly

to

the

rapid

proliferation

of

gen

AI,

a

development,

the

report

says,

that

has

put

lawyers

to

the

test.

“Judging

from

the

2024

Future

Ready

Lawyer

Survey

results,

they

seem

to

have

jumped

on

the

gen

AI

train

more

rapidly

than

they’ve

ever

jumped

on

new

technology

before.

It

is

a

promising

development,

which

says

a

lot

about

the

agility

and

adaptability

of

legal

professionals.”

Chris

Chris

Kathryn

Kathryn