Langton Chiwocha chose Emmerson Mnangagwa among 23 candidates in Zimbabwe’s presidential elections a year ago. Today he says he deeply regrets his choice.

“We had high expectations as many promises were made, but things have turned worse since the elections,” Chiwocha said. “I wish I could take back my vote, or maybe I shouldn’t have bothered to vote at all.”

Mnangagwa, 76, who took over from long-time autocrat Robert Mugabe, went into the July 30, 2018 elections vowing to revive Zimbabwe’s sickly economy, end cash shortages, mend fences with former western allies and lure foreign investors.

Mnangagwa launches investigation into brutal security forces crackdown, promises ‘heads will roll’

Chiwocha, who holds a business studies diploma from a college in the capital Harare, says his hopes have been cruelly dashed.

“I graduated in 2012 and I have not had a job. I thought after winning the elections, Mnangagwa would fix the economy and all who had qualifications would get jobs.”

But within months of Mnangagwa’s election, the ghosts of Zimbabwe’s economic past returned: severe power rationing and shortages of fuel, bread, medicine and other basics.

In June this year, the annual inflation rate hit a decade-high 175 per cent. Memories revived of the terrifying hyperinflation that reached 500 billion per cent in 2009, wiping out savings and wrecking the economy.

That episode ended when the US dollar became the national currency, replacing the Zimbabwean dollar, which had been proudly introduced upon independence in 1980.

But in June, Zimbabwe in theory ended the use of dollars, replacing them with “bond notes” and electronic RTGS dollars, which would combine to become a new Zimbabwe dollar, a currency that has yet to be introduced in paper form.

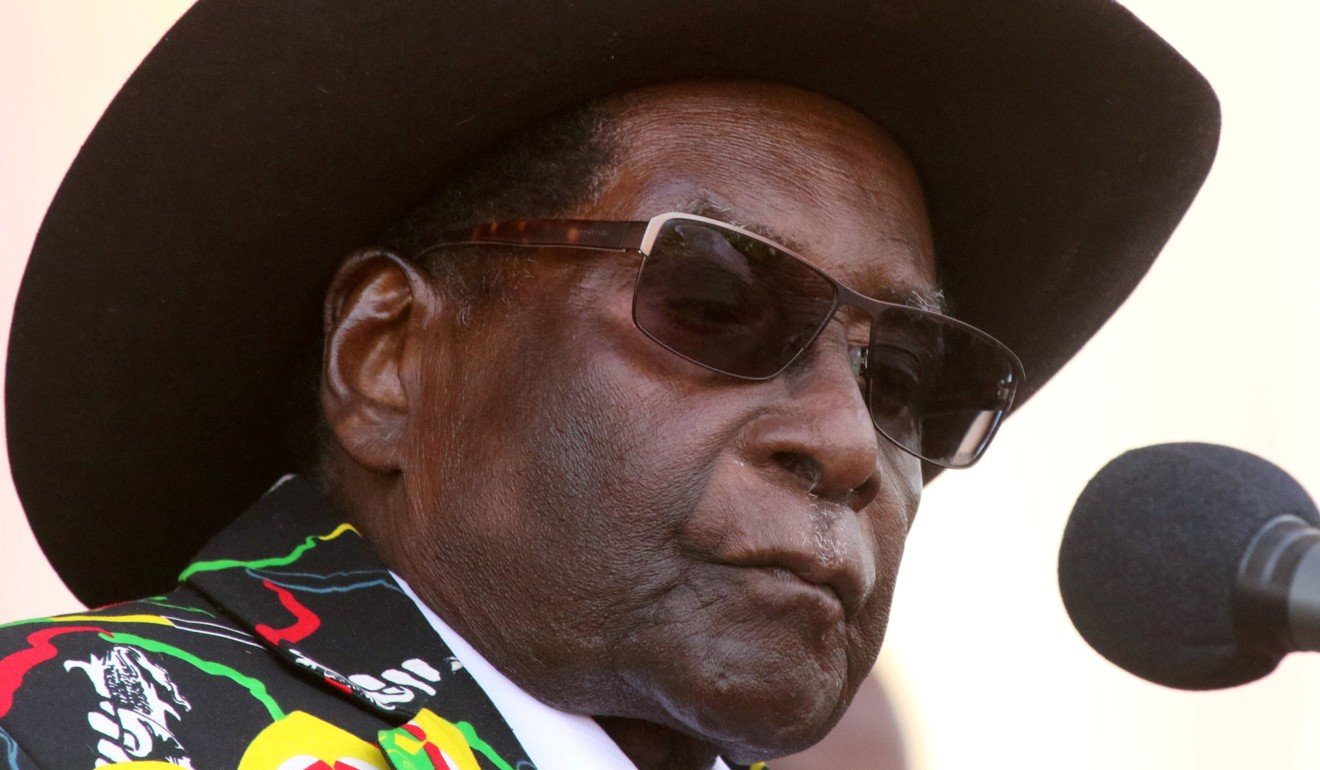

Former president Robert Mugabe. Photo: Reuters

Zimbabweans say it is a nightmare to get common documents such as passports, drivers’ licence discs and vehicle registration plates – the government is too poor to import the materials to make them.

Over the past two decades, hundreds of thousands of Zimbabweans have fled abroad seeking work. Many others are now seeking to join the exodus as the economy withers.

“We are sitting in a vehicle whose wheels have fallen off,” said Derek Matyszak, a senior researcher at a South African think tank, the Institute of Security Studies. “Nothing is moving”.

“Mnangagwa was fully aware that Mugabe had left behind an economic disaster. To get out of it required re-engagement to attract investment from wealthy countries, improved governance and respect for human rights.”

Two days after the election, at least six people were killed when soldiers opened fire on protesters demanding the results of the ballot be published.

In January, at least 17 people were shot dead and scores injured as soldiers were ordered to crush nationwide protests triggered by a doubling of fuel prices.

“The events of August 1 last year and January this year have set back the re-engagement effort and possibility of a bailout,” Matyszak said.

Power is usually turned on between 10pm and 5am – at other times, businesses are at a loss to know whether they will get electricity.

Mugabe’s exit will make Zimbabwe even closer to China, say Chinese analysts

“Factories and industries will not open for the duration of the power cuts,” Matyszak said. “That’s hours of production lost. It means Zimbabweans are going to sink deeper into the hole.”

Tony Hawkins, a professor at the University of Zimbabwe’s School of Economics, agreed.

“It’s very difficult to be anything other than pessimistic and negative at the moment,” he said. “Jobs are being lost and exports are being lost. The fact is you are not going to get the economy back on the rails without some kind of accommodation with the main opposition.

“Without that accommodation, chances of getting international recognition and support are slim. They [the government] are caught between a rock and a hard place. It’s a very difficult situation and there is no short-term way out.”